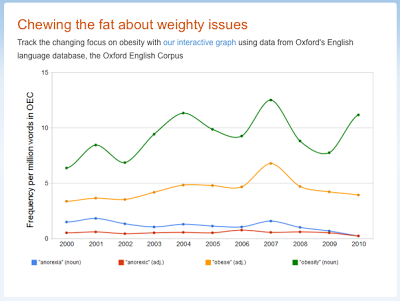

My eyes are so keen on eating disorder talk that I mistakenly thought our culture had been talking about eating disorders with increased frequency. Oxford English Dictionary proves me wrong: Mentions of the word anorexia in the English canon have stayed fairly steady over the past decade. Unsurprisingly, though, we've been talking about obesity more than we used to:

The entire entry at OED is worth reading, and it prompts a few thoughts on my end:

OED notes that even though anorexia was dwarfed in mentions by obesity, during this time period the number of "spinoff" words based on anorexia was manifold. Obesity gave us diabesity and globesity (which I'd never heard of until this article); anorexia, on the other hand, gave us orthorexia, tanorexia, manorexia, permorexia, bleachorexia, bigorexia, and bridorexia. Some of these are terms that may be adopted into legitimate medical language; orthorexia (obsession with a healthy diet) and permorexia (chronic dieting), though not widely used by the medical community, would both fall under the umbrella of ED-NOS, or eating disorder not otherwise specified. Some are a misunderstanding of eating disorders: Men can be anorexics, making manorexia superfluous, even a mockery of men who wrestle with an eating disorder. Others co-opt medical language to create a problem where there isn't any: I'm sure there are people who are obsessed with whitening their teeth, but it's not a disorder, is it?

Why the casual co-opting of anorexia while leaving obesity alone? It's not like we as a culture shy away from poking fun at fat people. I think it's because even as our culture pities the anorexic, we're also more eager to identify with her—and diminish her. Developing an acute case of "bridorexia" sounds better than developing "bridesity," though certainly it's not unheard of for women to gain weight before their wedding from stress-related overeating. We may cluck at the former, but we ignore or shame the latter; we can't glamourize it with a sweet little suffix. A better term for tanorexia might be willful path to melanoma, but tanorexia is adorable and sort of harmless. As seriously as we take anorexia, we're also eager to belittle it by making it seem as optional as teeth-whitening. We affix the -orexia because that signals that it's a compulsion—but a cute, girlish compulsion. It's the -ette, -ina, and -trix of disease suffixes.

2) Our bodily attentions are fickle.

Notice when mentions of both obesity and anorexia dropped? Right around when the stock market did. This makes sense, of course—the economy was in crisis, and frankly it felt more important to focus on what was happening with the S&P 500 than with our bodies. (In an oddly refreshing twist, I remember losing my job in October 2008 and suddenly realizing that after a week of mourning, freaking out, and drinking, for the first time since 1983 I'd gone seven days without giving the size of my body a single thought.) But it also points to how much "obesity crisis" reporting boils down to a trend piece. I'd wager that, ironically, eating disordered behavior—both the kind that results in obesity, and the kind that results in anorexia—increased during this time, as stress of any kind is a primary trigger for eating disorders.

3) Obesity comes in His & Hers colors.

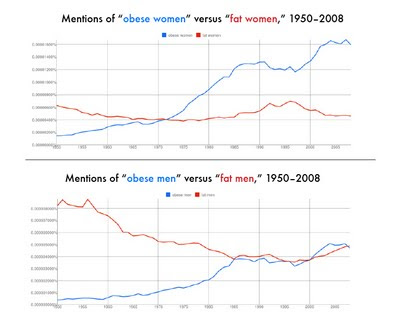

The Oxford English Dictionary graph got me thinking about the relatively sudden shift from fat as an appearance issue to obesity as a health issue. I see the relatively recent emphasis on body size as a marker of health—as opposed to simply a marker of hot-or-not—as being designed in part to create a fact-based path to reprimand heavy people for their size. There's no doubt in my mind that this is gendered: We as a culture love to examine women's bodies, and having a "legitimate" reason to do so—I'm just worried about your health, honey—gives us carte blanche. Look at the incidence of the term "fat women" and "obese women" as opposed to "fat men" and "obese men", as charted through uses in all Google Books published between 1950 and 2008:

If this were truly a case of reconsidering the term fat, or of the heightened cases of the medical term obesity (which only means "excessively fat," after all), or of a shift in the way that we report and record these terms, the charts would look roughly similar for both sexes. But they don't: We suddenly found a lot more "obese" women to write about (she-besity?) compared to steady numbers of "fat" women, whereas in the mid-'80s, we started writing about "fat men" and "obese men" as if they were one and the same.

Regardless of how you feel about the term fat—or obese, big, heavy, plus, zaftig, or slender, trim, thin, or skinny—data like this points to how what we're describing with these terms often isn't really a body at all. We're judging our fears and desires alongside the target's shape and size; we're evaluating our cultural attachments to bodies, not the bodies themselves. Once we're able to step back and see that, I'm guessing we'll be one step closer to not judging one another's bodies at all.

The entire entry at OED is worth reading, and it prompts a few thoughts on my end:

1) We love anorexia riffs. Obesity, not so much.

Why the casual co-opting of anorexia while leaving obesity alone? It's not like we as a culture shy away from poking fun at fat people. I think it's because even as our culture pities the anorexic, we're also more eager to identify with her—and diminish her. Developing an acute case of "bridorexia" sounds better than developing "bridesity," though certainly it's not unheard of for women to gain weight before their wedding from stress-related overeating. We may cluck at the former, but we ignore or shame the latter; we can't glamourize it with a sweet little suffix. A better term for tanorexia might be willful path to melanoma, but tanorexia is adorable and sort of harmless. As seriously as we take anorexia, we're also eager to belittle it by making it seem as optional as teeth-whitening. We affix the -orexia because that signals that it's a compulsion—but a cute, girlish compulsion. It's the -ette, -ina, and -trix of disease suffixes.

2) Our bodily attentions are fickle.

Notice when mentions of both obesity and anorexia dropped? Right around when the stock market did. This makes sense, of course—the economy was in crisis, and frankly it felt more important to focus on what was happening with the S&P 500 than with our bodies. (In an oddly refreshing twist, I remember losing my job in October 2008 and suddenly realizing that after a week of mourning, freaking out, and drinking, for the first time since 1983 I'd gone seven days without giving the size of my body a single thought.) But it also points to how much "obesity crisis" reporting boils down to a trend piece. I'd wager that, ironically, eating disordered behavior—both the kind that results in obesity, and the kind that results in anorexia—increased during this time, as stress of any kind is a primary trigger for eating disorders.

3) Obesity comes in His & Hers colors.

The Oxford English Dictionary graph got me thinking about the relatively sudden shift from fat as an appearance issue to obesity as a health issue. I see the relatively recent emphasis on body size as a marker of health—as opposed to simply a marker of hot-or-not—as being designed in part to create a fact-based path to reprimand heavy people for their size. There's no doubt in my mind that this is gendered: We as a culture love to examine women's bodies, and having a "legitimate" reason to do so—I'm just worried about your health, honey—gives us carte blanche. Look at the incidence of the term "fat women" and "obese women" as opposed to "fat men" and "obese men", as charted through uses in all Google Books published between 1950 and 2008:

If this were truly a case of reconsidering the term fat, or of the heightened cases of the medical term obesity (which only means "excessively fat," after all), or of a shift in the way that we report and record these terms, the charts would look roughly similar for both sexes. But they don't: We suddenly found a lot more "obese" women to write about (she-besity?) compared to steady numbers of "fat" women, whereas in the mid-'80s, we started writing about "fat men" and "obese men" as if they were one and the same.

Regardless of how you feel about the term fat—or obese, big, heavy, plus, zaftig, or slender, trim, thin, or skinny—data like this points to how what we're describing with these terms often isn't really a body at all. We're judging our fears and desires alongside the target's shape and size; we're evaluating our cultural attachments to bodies, not the bodies themselves. Once we're able to step back and see that, I'm guessing we'll be one step closer to not judging one another's bodies at all.