"What is a sexy woman? Very simple. She is a woman who enjoys sex," wrote a woman whose most famous product many mistakenly blame for our occasionally uneasy relationship with sexy—the godmother of Cosmopolitan, Helen Gurley Brown. I'm with her, though: I like sexy. Sexy can be innocent; sexy can be democratic; sexy can be deliberate or unknowing or shared or solo. Sexy has little to do with appearance. It has to do with sex, which most of us can do, and all of us can think about. If I'm feeling terrifically unsexy, I can dance around to The Troggs in my living room wearing a BUtterfield 8-style slip for a 10-minute cure. When I don't feel beautiful, however, the remedy is more elusive.

We started using sexy to merely mean "engrossed in sex" in 1905, a mere four years after the official end of the Victorian era. It inched closer to meaning erotic with its broadening use: Feminist Charlotte Perkins Gilman used the term when discussing the "perverse dress practices" of Ourland, the gender-dystopia she created in 1915, placing her among the first to apply the word to how we style ourselves.

With this early semi-endorsement from a feminist, then, it's no surprise that from its inception, sexy has been used unisexily, describing men as well as women. Etymologists point to Rudolph Valentino as the first person to be described as sexy, in 1923. Women still took the lead, naturally—but looking at literary sexys from the first half of the century, sexy people were still relatively rare. References to sexy things abound during this era: questions (Vanity Fair, 1930), books (The Nation, 1908), eau de toilette (Consumer Reports, 1940), cartoons (Finance, 1947), plays (H.L. Mencken on Noel Coward, 1928), voices (Billboard, 1943), dreams (Psychoanalytic Review, 1919), films (New Outlook, 1924, and songs (The Unitarian Register, 1938).

For more pictures of the world's first sexy person,

check out this beautiful photo book, curated by Donna Hill.

check out this beautiful photo book, curated by Donna Hill.

Still, sexy people popped up now and again, notably in the works of authors Myron Brinig (1941, describing a man) and Meyer Levin (1933, describing a woman). Even Gertrude Stein was described as sexy in The New Yorker in 1936—but these three are some of the only literary instances I found of sexy being used to describe individual people, not situations or things; the common thread here is that all are Jewish Americans. Which makes sense: Generally speaking, sex itself is treated more liberally in Jewish culture than in Christianity. After all, rabbis may marry, priests cannot; Talmudic literature endorses marriage while frowning upon celibacy, whereas until relatively recently, Christian marriage was viewed as a sort of second-best option to celibacy ("Renounce marriage and imitate the angels" wrote John of Damascus—or, hey, imitate Jesus, the original bachelor). It only makes sense, then, that the application of sexy to people might have originally gained traction from Jewish culture.

Sexy may have been the verbal word on the street, though, because critic Gilbert Seldes sure came down hard upon sexy in 1950's "The Great Audience," his takedown of the Hollywood Production Code. "The word commonly used in describing movies and movie actresses is sexy; the word commonly used to describe living people of strong sexual enterprise is passionate. Since the movies are forbidden to display sensuality, sexy is a proper adjective; it implies an as-if state, not an actual one," he writes. "Sexy refers to the superficial and the immature aspects of the relations between men and women, to the apparatus of seduction and not to the pains or pleasures if seduction succeeds; to provocation, not to satisfaction." It's a fair point—more chat, less kiss!—but from a contemporary view this is amusing, given that the Code yielded material we now reference as incredibly passionate, if veiled. (Sleeper car in North by Northwest, anyone?)

It's around here, then, that sexy might have begun to lose its plot—it hasn't unraveled completely, but I'd argue it may be inching toward misappropriation. Like many a word with potential for a generous application, sexy often takes on a narrowed meaning. (You will not be shocked to learn that a Google image search for sexy brings up a bevy of big-breasted white women in bikinis.) So Allyson's take on sexy at the excellent style blog Decoding Dress rings uncomfortably true. She examines sexy through the lens of Plato's Forms: What the essence of sexy is versus what our senses tell us are reasonable approximations of sexy. By seizing the essence of sexy—which is, after all, sex—instead of its avatars, one is able to have agency over sexiness, which explains the realization Allyson comes to about her presence as a woman who felt sexy in a particular outfit: "[The connection between feeling aroused and having an appearance that arouses another] is about power. The man who whistled at me, my spouse, and any other observer who experienced arousal were the objects of that power. My own experience of feeling sexy was that of being power's subject, the wielder of power [emphasis mine]. That power connects our experiences and is, in fact, the substance of them; without the power to arouse, sexy isn't happening." I've argued here before that the power of pretty is a false power, but Allyson successfully illustrates here how appearance can subvert the traditional subject/object relationship. In other words: A miniskirt, worn with the right intention, can be powerful.

Which brings us to the second half of the 20th century, and Helen Gurley Brown. The chapter "How to Be Sexy" in Sex and the Single Girl is part concrete advice ("Being able to sit very still is sexy") and part democracy of the sort I champion (see introduction). Her take on sexy is notable because Cosmopolitan was instrumental in making sexiness seem both normal and compulsory for women. (I once went to hear Cosmopolitan editor Kate White speak about coverlines, during which she addressed two of my personal favorites: "Sexy Sex" and "Erotic Sex.)

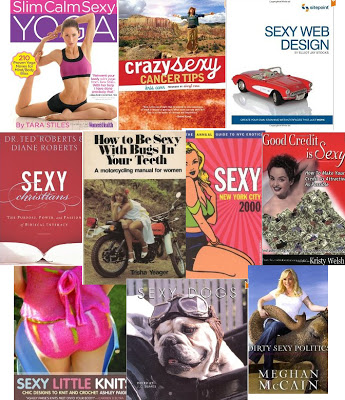

Cosmo's in/famous sex tips generated alongside tips on being sexy, which led to the now-ubiquitous sexy tips in the unlikeliest of places. We now know how to be sexy doing yoga, getting cancer, designing websites, becoming a better Christian (why let Gertrude Stein have all the fun?), motorcycling, visiting New York, upping your FICO score, knitting, being a dog, and being the daughter to a former presidential candidate.

Of course, Dirty Sexy Politics has little to do with sex (I hope/assume; I haven't read it), which begs the question of our contemporary application of sexy to things that have nothing to do with sex. Once sexy became the norm, its scope expanded indiscriminately: A 1970 issue of the journal Nuclear Industry "introduces tough, non-sexy questions about nuclear power," and everything pretty much went out the window from there. Sexy began to mean anything generally appealing; Webster's now recognizes it as such.

I have no problem with this, except: The more we continue to divorce sexy from sex, the further we stray from its essence—or, as Plato-via-Allyson writes, its Form. Instead of broadening sexy when we apply it to McCaindom or nuclear power, we narrow its application to people. Just as Paris Hilton's rendering of hot has made me turn away from the word and see it as the province of the tanned and hairless when it needn't be (as commenter Nine recently wrote on my "hot" entry, "I find the word pretty egalitarian in terms of not being tied to mainstream beauty standards"), the more we make sexy meaningless, the more we allow it to become seized by those who lay the loudest, splashiest claim to it. When Victoria's Secret hinges a campaign on issuing an annual list of "What Is Sexy," we push sexy further away from its essence and more toward its signals. Then, suddenly, instead of anyone being able to be sexy, we have to qualify certain people as "ugly sexy" (or "Sexy Ugly," if you're Lady Gaga), not plain old sexy. People like Willem Dafoe, Tilda Swinton, Sandra Bernhard, Steve Buscemi, all of whom made Nerve's list of the uglysexiest people around: These are some downright sexy people, folks, even if they're not what we think of as pretty (though in my estimation they're hardly ugly). Why do we need the nasty little qualifier of ugly?

Don't get me wrong—I'm glad that we have a term for people whose magnetism and inner heat, not their perfectly crafted features, is what draws us to them. It's just that we had a perfectly good word already.