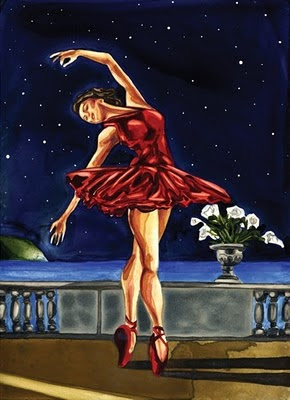

Like fragments of an ongoing daydream, artist Annika Connor’s lush watercolors focus on the feminine aesthetic in beauty—lovers in an embrace, ballerinas in flight, even decadent interiors. Annika’s work also extends outside of the studio; she’s the founder of Active Ideas Productions, which promotes emerging artists through education, publications, and more. The impetus to talk with Annika was, of course, her intriguing work, which frequently captures beautiful women in intimate moments. But I was also particularly eager to learn more about her thoughts on personal beauty and presentation: Even in the fashion capital of the world, she stands out as exceptionally stylish (legendary New York Times style photographer Bill Cunningham agrees; he’s photographed her several times) and effortlessly glamorous without sacrificing any of her natural warmth. In her own words:

On Seeing and Being Seen

I got glasses a couple of years ago for distance, and when I did I was like, “What?! You’re supposed to see all that?”

[Laughs] I couldn’t believe that I was supposed to see the branches on trees 50 feet away—that’s nuts! That’s way too much information! When I go to the ballet or the museum I'll put on my glasses; other than that, I don't tend to wear them. I kind of like seeing what's in front of me and letting the rest be a little blurry. So I don't really notice people on the street very much, or notice them noticing me—I get lost in this little bubble.

[Laughs] But I don’t take the glasses off in order to not see people; it’s just a byproduct.

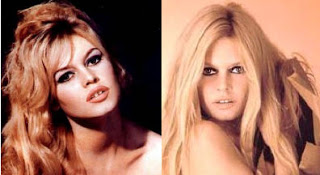

Marilyn Multiplied

I started this around the time I got glasses—

Marilyn Multiplied, and it's obviously playing on the Andy Warhol idea. This is from

How to Marry a Millionaire, where Marilyn Monroe plays this bumbling sort of fool because she has to wear strong prescription glasses, but she doesn’t want to. She’s this great comic character—she’s doing all these silly things because she can't see what's going on. In this particular scene, she's gone into the bathroom, she's had her glasses on, she's fixed her hair, she's fixed her makeup, she's straightened her dress, and here she's just taken off her glasses and she's putting them back in her handbag. So this painting is depicting the moment when she's decided to literally not see the world in order to be seen by the world as beautiful. She's playing a comic character, but it struck me as poignant that

her character was deliberately operating blind in order to be seen. When I painted her reflections—they're all her, but they could almost be different women too. Overall the painting is about the various multifaceted sides one has, all the many women that one woman is, depending on the angle or the light or their mood.

Any flat surface functions as something you gaze at—there's an immediate association with the mirror. So a painting, although it doesn't actually reflect your image, often functions as a mirror, both to the viewer and the artist. As an artist, it's hard to keep yourself out of your paintings. My paintings almost always have a self-portrait element, even if I’m painting a man or a forest, so when I am painting women, it’s natural that I project a bit of myself into them. Of course my mixed emotions and feelings also go in there on some level, but my paintings take a really long time to make, and my emotions change, so it’s not necessarily as direct as: I’m angry, and then the woman looks angry.

La Goulue

On Allure

I titled this painting

La Goulue, which was a great restaurant on the Upper East Side but which also translated means “the greedy one.” I gave her this name because in this painti

ng she’s so greedy for the viewer’s attention. I was inspired by a Stieglitz photo of a woman looking at the viewer, sort of hanging over a sofa wearing a come-hither look that seems to say, “Look at me.”

In my studio, I actually had to hang La Goulue behind my sofa because she was so demanding of your attention that if she was on the other wall it was interfering with the ability to see my other work. I love that she’s really insisting having on the viewer’s eye on her, but no, I don’t think I need to make sexy paintings in order to get the viewer’s attention. When I make sexy painting, it is because my work in part deals with depicting romance and daydreams, and sex and allure is a part of that conversation.

I have a lot of notions that are feminine and super-idealistic—some might say idealistic or naive. However,

there's so much in the world that’s unpleasant, unattractive, uninteresting, and aggressive—if I have the opportunity to literally make something that never existed before, like a painting, why shouldn't I create something that's inspiring and uplifting and beautiful, as opposed to something that’s jarring? I definitely feel that by seeing the world as beautiful, I end up painting a world that is somewhat beautiful.

On Self-Presentation

I want to give gifts to my viewer, and I suppose that kind of extends with my love of fashion and how I present myself. If I’ve put myself together in the best possible way that is the most appropriate for the situation, it makes me feel confident. So for example, if I meet with my lawyers, I’ll put on a great suit, I’ll pull my hair back, I’ll look all...Corporate Annika. Doing this sort of attire makes me feel competent and I’ll ask questions about

[faux-deep voice] intellectual property law.

Sometimes there's a theatrical element to what I’m wearing, a bit like costuming. Presentation is a big part of pulling together a look. When you put a frame on a painting, it’s the final touch. And a pretty dress without any accessories or makeup—something feels missing. Jewelry, makeup, hair—it's how you frame the figure. It's similar to how you paint a painting.

During the day I don’t wear much makeup, just the basics to make me look like I don't have dark circles under my eyes. But if I’m getting dressed up for an event, I enjoy doing something dramatic. That's one of the best things about being a woman—we can make ourselves look way more beautiful.

I sometimes feel bad for men. They don't get to wear cover-up! That must suck! They just have to look how they look.

At the Les Liaisons Dangereuses: The Young Fellows Ball; photo, Yina Lou

As a woman, when you know you're looking good, you feel confident. Your day is better, you accomplish more, you meet more people, because you have that extra edge. Sometimes when I'm feeling blue, I'll put on an outrageous outfit and go to Whole Foods and grocery shop. The great thing about Whole Foods at Columbus Circle is that everybody goes there. You have no idea if somebody's just stopping and getting some food on the way to a dinner party, so I can totally be in a ball gown at Whole Foods if I feel like it!

So when I am sad I'll put on an outrageous hat or I’ll wear a super-colorful outfit, so people will smile at me. And maybe it's a bit because they’re laughing, but

in the end when you’re walking down the street and people are smiling at you, you start to feel better, even if you had been sad.

Left: At the Performa Red Party; House of Diehl created the umbrella bustle on-site; photo, Yina Lou.

Right: At the Veuve Cliquot Polo Classic.

On Actions and Reactions of Others

Obviously I notice when a guy catcalls or something like that—but I learned while living in Barcelona that that is a compliment. Of course, you can get offended by it from a feminist perspective, but essentially they're paying you a compliment. There's certain ones I don’t like, but for the most part when I'm walking down the street and some guy is like, "Ooh, looking good!” it makes me smile. Maybe I shouldn't, but—I mean, "Ooh, looking good!"

[Laughs]

I don't feel I get belittled for being feminine, because I'm embracing it. My hair is blond and I’m wearing a sequined dress—if the first guy I'm speaking with doesn't immediately take me seriously and think I'm, like, this crazy intellect, that's totally okay! When that person eventually hears my ideas, my smarts will show themselves.

Actually, it's sort of good when people underestimate me, because then it's easy to impress them.

[Laughs] And they do—

I tend to get underestimated. But when they see my work, the painting speaks for itself.

Held back by beauty? Honestly, I don't really see myself as a beautiful woman. I see myself as, you know, moderately attractive. I'm okay, but I’m not any kind of supermodel. So maybe if you're super-super good-looking, you get pigeonholed by that. But I'm not good-looking enough to be held back because of things like that.

[Laughs]

On Fascination

Beauty encourages projection because it engages with fascination: Something that's really beautiful fascinates you. You want to keep looking at it, whether that’s sunshine through yellowing leaves in Central Park on a lovely Sunday, or a woman simply strolling by.

Because beauty is evocative, you relate what you're seeing with what you're remembering. When you’re looking at a beautiful landscape, you're enjoying the transcendental moment, but you’re also remembering, say a hike you took with your mother some other time. So when you're seeing a beautiful painting and it reminds you of an experience you had, or someone you knew.

A beautiful woman can remind you of someone you know, or almost someone you can imagine you want to be.

Midnight Express

But I also think there is a flipside to the beautiful.

In order for something to be truly beautiful, there has to be fragility, or perhaps a potential of destruction. Everybody says beauty is fleeting—it this sense that beauty won't last forever which is part of why it its hypnotizing.

I also think people project with beauty because

there's a longing that comes with the beautiful—a longing to possess, a longing to be there, a longing to become, depending on what the subject is. That longing can contribute to that darker side of the beautiful. And that darker side can intoxicate, intrigue, and destroy.

Rivera Remembered