Peggy: Should we get lunch?

Joan: I want to burn this place down.

Peggy: I know, they were awful, but at least we got a yes. Would you have rather had a friendly no?

Joan: I don’t expect you to understand.

Peggy: [With demonstrated doubt] Joan, you’ve never experienced that before?

Joan: Have you, Peggy?

Peggy: I don’t know—you can’t have it both ways. You can’t dress the way you do and expect—

Joan: How do I dress?

Peggy: Look, they didn’t take me seriously either.

Joan: So what you’re saying is, I don’t dress the way you do because I don’t look like you. And that’s very, very true.

Peggy: You know what? You’re filthy rich. You don’t have to do anything you don’t want to do.

Sorry, Ladies: There Won't Be a World Hair Cup for Women

Miyoko Hikiji, Soldier, Author, and Model, Iowa

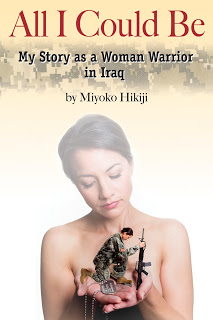

“I feel obligated to educate anyone that doesn’t wear a uniform about what military service is like,” says Miyoko Hikiji, a nine-year veteran of the U.S. Army whose career began when she joined the Iowa Army National Guard in college, eventually leading her to serve with the 2133rd Transportation Company during Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003. Her recently published book, All I Could Be: My Story as a Woman Warrior in Iraq (History Publishing Company, 2013), goes a good ways toward that obligation. And when I found out that the soldier-turned-author also began modeling upon retiring from the military, well, how could I not want to interview her? Beauty is hardly the most crucial aspect of a soldier’s life, but it’s an area unique to female soldiers, who make up 15.7% of active Army members—and who, in January, had all military occupational specialties opened to them, including combat units previously closed to women. Hikiji and I talked war paint, maintaining a sense of identity in extraordinary circumstances, and Hello Kitty pajamas. In her own words:

On-Duty Beauty

Military rules about appearance are pretty strict. Your hair has to be tied back in a way that doesn’t interfere with your headgear and that is above the collar of your jacket. That pretty much leaves it in a tight little bun at the nape of your neck. Once you get your two-minute shower and get out soaking wet, you just braid it together and it stays that way all day. After a mission or training, most of the women with longer hair wore their hair down, because having it in a bun under a helmet is really uncomfortable. In Iraq I might have had eyeshadow, from training and preparation before we actually got to Iraq. When we’d be in civilian clothes I’d have a little makeup for chilling out. But once I was actually in Iraq, I was more focused on sunscreen, moisturizer, vitamins. I just wanted to be healthy. And I had a stick of concealer. I wore that for some of my scars—there were a lot of sand fleas, and I had bites all over my body.

I couldn’t really approach trying to cover them well and look nice when I was there; I just needed to be clean. When I came home I did microdermabrasion for months to get rid of the scars. And I couldn’t wait to get regular haircuts. I also got my teeth whitened—we took daily medicine to protect against infection and malaria and stuff like that, but it makes your teeth turn yellow.

In Kuwait I think we got a shower once every three days. We took a lot of baby wipe baths. Those lists that say, Send this to the troops—baby wipes are always on there. I did try to get my hair washed as often as I could. A lot of women would put baby powder on their hair and brush it out, to absorb the oil and the dirt. I’d just dump canned water over my head if that was the best I could do. If I was up by the Euphrates I would shave in the river if I had a chance, but that was something you didn’t get to do very often.

On War Paint

The idea of makeup as war paint is interesting. Actual “war paint”—camouflage paint—is like a little eyeshadow pack, so in camouflage class or in the field, you’d have a woodland one that has brown, two shades of green, and a black. You’d put the darkest colors on the highlighted parts of your face so they’re subdued, and then you kind of stripe the rest across your face. It’s extremely thick, almost like clay; you wear it and you sweat in it and it’s just there. It’s kind of miserable! But if you look at yourself in the mirror after doing these exercises with the camouflage paint on, it’s hard to look at yourself the same way. There really is something to putting on the uniform or the camouflage, or just the effect you have when you’re holding a loaded weapon. All that contributes to your behavior. So I definitely feel different when I wake up and put my regular makeup on.

I approach the world differently, and the world treats me differently. What is it that we’re fighting? That’s hard to say. On some levels, I feel like when I wear makeup I’m buying into the whole thing of what a man tells me looks pretty, or that I’m kind of giving up part of my natural self. But then I justify it by saying, Well, it works, or Well, I’m getting paid to do that right now, with modeling. There is a lot of conflict there. It’s sort of a war on self, sort of a war on womanhood.

On Modeling

There was a tactical gear company filming some commercials at Camp Dodge, where I trained. They were going to have the actors go through an obstacle course I’d been through, doing everything at the grounds that I’d been training at for years. At the audition they said, “We’d like for you to have weapons experience, because we’re gonna shoot some blanks out of M-16s.” I thought, There’s no way I’m not gonna get this part. And then I didn’t. They picked people who were bigger, probably a little gruffer. People who looked the stereotype of what you think a soldier looks like.

To be fair, I don’t know all their criteria, so it’s easy for me to say they thought I was too pretty, too feminine. I don’t know that. But I do know that people who were picked for that modeling job didn’t have more experience than I did. Certainly none of them had weapons experience like I did. I think that they just didn’t believe that I fit the bill of looking like a soldier.

My experience in the military couldn’t have been anything but a benefit to anything I did in the future. Whenever I have a modeling job I always show up on time or early. I always have everything I’m supposed to have—not only do I print it out, but I check it just like a battle checklist. I look at every project like a mission. When I get there, I always have enough of whatever is needed to take care of somebody else who’s not prepared, which would be a squad leader’s position. I’m used to all that, and the people I work for are usually kind of surprised. In the middle of a job, if something happens, I’m okay with cleaning it up, whereas maybe other models or actresses might feel like that isn’t what they’re being paid to do, or that it’s a little below them. But you do so many crappy jobs in the military. You burn human poop! You have a bar for what you’re willing to do, and mine is all the way at the bottom. Things just don’t bother me or gross me out.

My great-grandmother was born in Japan, and my grandmother and my father were born and raised in Kauai. Being part Japanese adds another element to modeling, especially in Iowa, where the population for minorities is so low. There’s a Colombian model and a Laotian model here, so it’s kind of a joke among us when the call goes out for these jobs—which minority are they going to pick? And for scenes with couples, there are people they’ll always pair together and people they never will. Last commercial I did, I was paired with a guy who was just Mexican enough. They’ll pair me with a black man, but they don’t pair a black man and a white woman together—I’ve never seen that for a commercial shoot. I’m half Czech also, but they use me for the Asian slot, and then they try to Asian me up. They’ll tell the makeup artist, Can you make her look just a little more Asian? It’s like, I know we’re filling the Asian slot, but we’ve got to make sure it actually looks like she is.

All I Could Be: My Story as a Woman Warrior in Iraq, Miyoko Hikiji, History Publishing Company, 2013; available in Barnes & Noble bookstores and online

On Uniformity

One thing I thought was funny was pajamas. All the guys slept in their brown T-shirt or just their boxer shorts, because it’s not like guys wear pajamas; that wouldn’t be acceptable in that world. But all the women had pajamas! And it was always something funny, like Rainbow Brite or Hello Kitty or something. At that point in the night we just wanted to be girls. On active duty, if it was a three-day weekend, you could wear civilian clothes to the final formation before being cut loose for the weekend. The guys looked basically the same—they’d wear jeans and a T-shirt, but they wouldn’t really look different. But if I showed up in a dress, they just couldn’t believe it! Women can have a lot more faces than men can have—men can’t change their appearance the same way women can, especially in a situation where they all have short hair. But a woman really does look a lot different in her civilian clothes, and I was one of only a few women in a unit that had just opened its ranks to women when I first joined in ’95. So the guys kind of looked at me like, Is that really the same person? I think it confronted them a bit about who exactly I was.

There was also a conflict around presenting a different face to myself. When I was wearing a uniform I felt a little tougher, like I was blending in better with the guys. I didn’t really look like them, but at least I looked more like them than when I was wearing civilian clothes. And when I’d be in a situation where I’d look nicer, sometimes I wouldn’t even tell people that I was in the army—sometimes I would, if I was in a mood to challenge stereotypes. But the two identities don’t seem to fit well because of the stereotypes we have—tough people are supposed to look gritty and dirty and cut-up with tattoos. And then people who are attractive—well, that’s not supposed to be tough at all. The movie G.I. Jane was a terrible depiction of that. Even though it tried to be a girl power movie, in order for Demi Moore to be one of the guys, she had to look like a guy. She had to shave her head because that was how she could reach that level.

I think that’s a real issue in the military—and in our society—about beauty and gender stereotypes, that pretty can’t be tough. It became kind of a side mission of mine. Whenever anyone entered the room and said, “Hey guys,” I’d say, “Wait, what about me?” They’d say, “Oh, you know we mean you too.” Well, no, not really, because I’m not a guy. I wanted to point out that I’m doing the same job, but I’m not really one of you. That’s okay, we’re different—as far as the mission is concerned we’re basically equal, but we do do things differently. It’s not a bad thing!

But let’s recognize who is it that the women are, because a lot of times I think we feel women have to be assimilated into manhood as a promotion into soldierhood, because we don’t think about soldiers as being women. We just think about them as being men. In the beginning I was so eager to assimilate and be accepted. I was okay with losing a bit of identity because I was becoming this new and different and better person—I was going to be a soldier and that was more important to me at the time than preserving some sort of identity as a woman. But by the time it got to the end of my military career I looked at things differently. In Iraq, on laundry day there would be clothes hanging out on lines that people would just string up wherever you could find a space, and some women had Victoria’s Secret underwear and lacy bras. At first I thought, What in the world? I don’t need a wedgie in the middle of a mission. But by the end it made sense to me, because we lost everything while we were there.

We lost our privacy; we lost a lot of our dignity. We were asked to do things that people probably shouldn’t be asked to do. So if you can hang onto something that is meaningful to you—whether that represents your femininity or your strength or your individuality, which we lost also—then what difference does it really make? It means something to them. Everybody has to find their thing to help get them through. You know, men don’t have to drop a lot of their stuff when they get deployed, but there’s a lot of pressure on women to change, to fill those soldiers’ shoes. The military uniform takes away women’s body shape; you don’t really have hips anymore, or a bust. It makes you realize how much just being a woman and being seen as a woman, let alone being attractive, plays into your life, because suddenly all that’s kind of gone.

Do Lipstick Feminists Actually Exist?

Now, don’t get me wrong: I’ve met plenty of feminists who wear lipstick. (It will probably not shock you to learn that this blogger indeed is one of them, both literally—lipstick corollary, yo!—and figuratively, as in, duh, look at this blog.) In fact, when I took a quick Twitter survey the other day, that was the number-one response I got: I’m a feminist, and I wear lipstick, but I’m not a lipstick feminist—followed by, I’m not exactly sure what that is.

Lipstick feminism, as I’ve seen it used (in accord with that highly reliable source of all wisdom, Wikipedia), is the idea that conventionally feminine hallmarks—lipstick and other cosmetics, heels, perhaps suggestive dress—can be a source of power for women, not simply a sign of one’s obedience to patriarchal requests. It’s somewhat related to the idea of “erotic capital” in that it seeks to render traditional signals of female sexuality as legitimate routes to authority—but feminism or some semblance of it, not money and other forms of capital, is the goal.

This is an intentionally friendly definition of lipstick feminism—in fact, if this description were what people were actually referring to when they use the term, I might on occasion identify myself by it (even as I’m skeptical of the idea that using one’s sexuality is a legitimate route to authority. It might be effective sometimes, sure, but it’s forever dependent on the mercy of people with actual power). But here’s the thing: Most times I’ve read or heard the words “lipstick feminist,” derision has been the intent. Sometimes it’s feminists explaining why the concept is bollocks; sometimes it’s from people using it to dismiss feminism wholesale. In other words, it’s a word we use to describe other people, not ourselves.

Not that this is restricted to lipstick feminism. Fact is, I can count on one hand the number of times I’ve heard a feminist qualify her feminism with any sort of label, even labels that were established by feminists themselves. Third-wave and second-wave are possible exceptions here, but not “official” schools of thought, even if any individual feminist generally adheres to one. And the reason we don’t tend to sort ourselves out by neat labels is that most of us believe a whole lotta things. I believe that legislative reform can be beneficial to women; I believe that men and women have some essential differences beyond mere biology; I believe gender oppression is linked to capitalism. So am I a liberal feminist, a cultural feminist, or a Marxist feminist—or am I just a feminist with a multifaceted approach to her politics, and indeed her life?

Yet you’ll notice that these various schools of feminist thought—which I’m guessing some women do stick to pretty strictly and would use to define themselves, though again, I can’t think of more than a couple of times that I’ve heard someone identify herself as an “[insert school of thought] feminist”—are named by their organizing approach and systems, not by their specific beliefs. That is, I can’t imagine anyone saying, “I’m a government-subsidized child care feminist” or “I’m a sexual violence feminist,” though both of these things fall under a feminist umbrella.

So enter “lipstick feminism”—hell, enter “pro-sex feminism,” which has always irked me because it implies that there are anti-sex feminists, and you’ve got to get pretty deep into an overly literal interpretation of certain strains of radical feminism before you’re going to find any of those. ("We so horny!") It reduces a concept that in some ways is simple (women = people!) and makes it simplistic, boiling down one of the most influential movements of the 20th century and putting a swivel cap on it. It trivializes feminism—hell, it even trivializes the questions implied by the term itself (can conscious exploitation of one’s own sexuality be a feminist act in some circumstances?). Like “pro-sex feminist,” it implies that there are feminists who are against lipstick, playing into that whole “feminists are ugly hairy-legged lesbians” stereotype that I thought we’d retired eons ago. And speaking of lesbians, isn’t the term “lipstick feminist” linguistically similar to the more established term “lipstick lesbian,” thus sapphically binding the two together in the listener’s mind?

But here’s the thing: Above all else, I’ve always believed that feminism—or any kind of social movement—takes all types. We need the Planned Parenthood canvassers I avoid on the street; we need the driven, unswayable voices you might describe as, yes, strident; we need nice-girl feminists who take pride in gently educating others about feminism; we need people whose response to teach me is don’t make me do your work for you. We need men; we need women-only spaces; we need people who reject a gender binary; we need people who use the gender binary to articulate the idea of a female essence and what that might mean. We need the marches and petitions; we need the quiet, life-changing transformations that take place in families over generations. We need the wearers of “This Is What a Feminist Looks Like,” and we need the “I’m not a feminist buts” too.

Which means we just might need lipstick feminists. So here’s what I’m wondering: Do you describe yourself as a lipstick feminist? If so, do you define it similarly to how I’ve defined it here, or do you have a different interpretation of the term? If you don’t call yourself a lipstick feminist: Do you think the term should be reclaimed? Is the label feminist-bait or is it a handy way of making the point that feminism needn’t be incompatible with beauty work?

(Thanks to Chelsea “Dipstick Feminist” Summers, Elisa “Pole Dancing Feminist” Gabbert, Rosalind Jana, Lacy “Eyeliner Feminist” of ModernSauce, Alyssa Harad, Rachel Hills, Nicole “Doc Martens Feminist” Kristal, Lily “Googling How to Get Red Wine Stain Off My Lips Feminist” Benson, Heli Lähteelä-Tabone, Cassandra Goodwin, and “Underwire Feminist” Bubbles for a set of thought-provoking and oft-hilarious answers to my Twitter inquiry on the matter.)

Two More Cents on Dove

I’ve heard from several readers who have pointed out that whatever quibblings I might have with the Dove campaign, the fact is that it’s better for women than traditional advertising, specifically the type that relies on sexist tropes. I agree: At the end of the day, if I had to choose between Dove’s “BFF marketing” style and the rest of ’em, I’d choose Dove. (And I’ll readily point out that the sketch artist ad “worked” on me: I totally got teary at the big reveal.) But as Cassie points out, we’re not limited to either/or options here, and as cynical as I might be about advertising, I'd feel more cynical if I just threw up my hands and said, Well, this is the best we can do, so I'll take it.

Yes, there’s an enormous problem with appearance-related self-esteem among women (and men). Yes, we need to continue to address this concern on a sociological level. Yes, it is incredibly painful for any of us in those moments of exquisitely vulnerable self-loathing. Yes to all that. And yet: Yes, most of us have looked in the mirror at some point and liked what we’ve seen. Yes, we look forward to wearing certain outfits because we know we look fantastic in them. Yes, we now snap so many self-portraits that we had to invent the word selfie to describe the phenomenon. Yes to all the natural human joy and pride and immodesty and pleasure we take in our looks. To deny that side of the beauty question is to deny our lived experience. To deny that side of the beauty question is to take shame in those moments of pride, to deny ourselves lest we be seen as thinking we’re “all that.” To deny that side of the beauty question is to publicly deny other women the same right we privately give ourselves. We don’t give ourselves that right all the time, no. But we don’t need to.

I’d be hesitant to put this thought out there, that maybe we like the way we look at the same time we don’t like the way we look—because really what I’m saying is that this is true for me, and my my, isn’t someone arrogant? But when I look at the numbers—the numbers we don’t hear about all the time in clucking tones—I see that my experience of beauty duality isn’t mine alone. Check out the numbers that writer and sociology PhD candidate Kjerstin Gruys points out: According to another study, 58% of women are satisfied with their appearance. 65% of women consider themselves “above average” in appearance. Or, hell, look at Dove’s own numbers from their 2004 research for the launch of the Real Beauty campaign: While only 4% of the Dove survey respondents copped to considering themselves “beautiful,” 55% of them were satisfied with their body shape and size. One of these numbers works in the narrative Dove is creating with the Real Beauty campaign. And one of them doesn’t.

Add to that the other structural concerns Virginia Postrel points out about the Dove video: We only see the results of seven women; 20 women participated in the initial experiment. (Did some of those women’s sketches fall out of line with the desired result?) The sketch artist—i.e. the person whose work the entire ad centers around—knew what the experiment while doing his sketches. There was no opportunity for women to correct the sketch as would happen if the goal actually were accuracy; how would someone know whether what she called her “long nose” differed wildly from the artist’s rendering of it?

And there’s that word beautiful, which, according to Dove research, only 4% of women describe themselves as being. What Dove doesn't tell you is how they came up with that number: They asked survey respondents to choose one word to describe themselves from a list of 10 words. Here’s a list of the words respondents were given to choose from (on page 10): natural, average, attractive, feminine, good-looking, cute, pretty, beautiful, sophisticated, sexy, stunning, and gorgeous. Does me choosing, say, sexy, or pretty, or natural or attractive signal a self-esteem problem? Hell, even choosing average doesn’t mean we're suffering—if you’re approaching the question from a statistical standpoint instead of an interpretive one (and some respondents undoubtedly would), by definition most of us would indeed be average. (Speaking of averages: When respondents were asked to place themselves on a “bell curve” of beauty, 13% of respondents said they thought of themselves as somewhat less or much less beautiful than other women. And 16% of respondents said they thought of themselves as somewhat more or much more beautiful than other women.)

But back to why I bothered to revisit the campaign in the first place: I think some of us have had enough. Just as Dove created the campaign in response to the fact that women had had enough of traditional advertising that asked us to feel lesser-than, it’s clear from the overwhelming response to the ad that while we’ve still had enough of that type of ad, we’re also becoming wary of the ads that use those feelings as leverage. And frankly, I’m thrilled to see such a variety of responses to the campaign. To me, it signals a desire to shed the therapeutic narrative of beauty. The question is: What narrative will we design in its place?

One Narrative Fits All: Dove and "Real Beauty"

Wearing Stigma

I’ve been thinking a lot about this Sociological Images post on managing stigma in the weeks since I first read it. I was struck by an anecdote it relates from journalist Brent Staples, a 6’2” black man, on why he started whistling classical tunes when walking down the street at night: “Virtually everybody seems to sense that a mugger wouldn’t be warbling bright, sunny selections from Vivaldi’s Four Seasons.” It provoked an instant sympathy—I sometimes find myself whistling without realizing I’ve started doing so, a habit I picked up from my father (who, like me, looks white), and the thought of using it as a tool of “I’m OK, you’re OK” sent a small stab through me.

But sympathy wasn’t necessarily the idea Lisa Wade was pursuing here; instead, she was writing of how stigma management calls attention to the ways that race, class, and gender are, among other things, performances: “In order to tell stories about ourselves, we strategically combine these things with the meaning we carry on our bodies.” And what sort of body is more loaded with meaning than that of a young woman? It’s impossible to think of the performance of femininity without considering the ways that the performance is an exercise in stigma management. And it's impossible to think of the ways women manage the stigma of their bodies without looking at fashion and beauty.

You’ll rarely see the word stigma in a fashion magazine, to be sure (though it could be a great brand name—“introducing Stigma by John Varvatos”), but so many fashion “rules” are simply sets of guidelines to managing the connotations of womanhood. The shorter the skirt, the lower the heel. The smokier the eyes, the more neutral the mouth. The tighter the pants, the more billowy the shirt. The more colorful the top, the plainer the bottom; the bigger the earrings, the smaller the necklace; the bolder the nail polish, the shorter the nail. I’ve seen all of these “rules” written out in fashion magazines and the like (which isn’t to say that there aren’t plenty of contradictory “rules” or guidelines on how to best break those rules, but these are generally considered to be within “good taste” instead of being fashion-forward), and what stands out isn't so much the rules themselves as the fact that they're presented without explanation. You're supposed to know inherently why you wouldn't pair a short skirt with high heels, a loud lipstick with a dark eye.

Now, some of these rules make a certain amount of visual sense: If you’re trying to showcase a gorgeous pair of earrings, wearing a bunch of other jewelry will just compete for attention. But other rules make visual sense only because we’ve adopted a collective eye that codes it as “right”—anything else betrays our sense of propriety. A micromini with four-inch heels? Coded as tramp. It doesn’t matter if the visual goal is to lengthen your legs, or if the woman next to you garnering not a single sneer is wearing a skirt just as short with a pair of low-heeled boots. You’ve failed to manage the stigma of womanhood correctly. You haven't made the right choices, the right tradeoff. You haven't found that ever-present marker of "good taste": balance. And while there are all sorts of stigma attached to womanhood, none is so heavily managed and manipulated and contradictory and constantly on the edge of imbalance as sexuality.

Complicating sexual stigma is something that’s closer to the permanence of race or ethnicity than these other fashion dilemmas are. (After all, fashion is a choice. You might be subtly punished for opting out of it altogether—or loudly punished for opting in but doing it wrong—but at least there’s a degree of control there.) If your body type is coded in a particular way, you’ve got a whole other set of stigma to deal with*. As Phoebe Maltz Bovy pointed out during her guest stint here, “[S]tyle and build have a way of getting mixed up, as though a woman chooses to have ‘curves’ on account of preferring to look sexy, or somehow magically scraps them if her preferred look is understated chic.” A woman with small breasts and narrow hips has more freedom to wear low-cut tops in professional situations without raising eyebrows, because there’s less stigma to manage. A woman in an F-cup bra with hourglass curves? Not so much. Witness the case of Debralee Lorenzana, the Citibank employee who was fired for distracting the male employees with her wardrobe—which, on a woman without Lorenzana’s figure, would be utterly unremarkable, and, more to the point, unquestionably work-appropriate. Her failure, as it were, lay not in her clothes but in not “properly” managing the stigma that her figure brought. (And when it came out that she’d had plastic surgery, including breast implants, internet commenters around the world engaged in a collective forehead slap.)

* In looking at my blog feed the other day, I noticed that I read a surprisingly large number of blogs written for busty women, given that I’m not one myself. But in this light, it makes sense: Many women with large breasts—particularly those who don’t wish to “minimize” their chests—have had to deal with a level of sexualization that my B-cup sisters and I don’t, or at least not in that particular way. So it only makes sense that bloggers who have had to think about their self-presentation in this way might have a good deal of sociological insight that comes out through their writing—which is exactly what I turn to blogs like Hourglassy and Braless in Brasil for, despite the fashions therein not being right for my frame. Consider this my official cry for small-breasted bloggers to take up the cause! C’mon, ladies, I want your insight and your tips on how to find a wrap dress that doesn’t make me feel like a 9-year-old!

Permission to Flirt

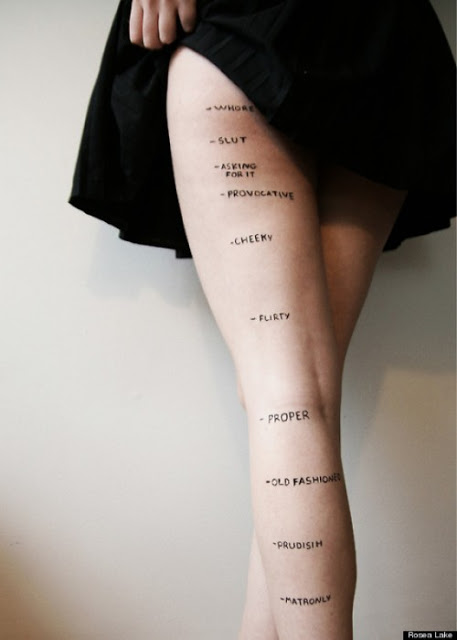

By now, you’ve probably seen art student Rosea Lake’s photo Judgments, which went viral earlier this month. Unlike, say, videos of children on laughing gas, this went viral for a very specific reason: It does what the strongest images do, namely that whole “worth a thousand words” bit. Judgments communicates the constant awareness of, well, judgments that women face every day we leave the house (and probably some when we don’t), and I won’t say much more about the actual image because it speaks well for itself.

That said, I’ve read commentary on the image that has also struck a chord, specifically Lisa Wade’s spot-on post at Sociological Images about how Judgments pinpoints the constantly shifting boundaries of acceptable womanhood, and then relates that to something women are mocked for: all those darn clothes (you know women!). “[W]omen constantly risk getting it wrong, or getting it wrong to someone. … . Indeed, this is why women have so many clothes! We need an all-purpose black skirt that does old fashioned, another one to do proper, and a third to do flirty....” Wade’s main point is an excellent one, as it neatly sums up not only what’s fantastic about the image but why women do generally tend to have more clothes than men.

But my personal conclusion regarding Lake’s piece was actually somewhat different: To me, it illustrates why my own wardrobe is actually fairly limited in range. The first time I saw it, I was struck by how effectively it communicates exactly what it communicates. The second time I saw it, though, I made it personal and mused for a moment about how save one ill-advised maxidress and one black sheath that hits just above the knee, literally every single one of my hemlines is within an inch of “flirty.” This is semi-purposeful: It’s a flattering length on me, and I’m a flattery-over-fashion dresser, so I’ve stuck strictly with what works. And isn’t it a funny coincidence that what happens to flatter my figure just happens to be labeled as “flirty” here, when in fact “flirty” is probably, for the average American urban thirtysomething woman, the most desirable word on this particular chart to be described as? (Depending on your social set you might veer more toward proper or cheeky, and of course I don’t actually know which of these words women in my demographic would be likely to “choose” if asked, but I have a hard time seeing most of my friends wanting to be seen as prudish—or, on the other end, as a slut.)

Of course, it’s not a coincidence, not at all. I may have believed I favored that hem length because it hits me at a spot that shows my legs’ curves (before getting to the part of my thighs that, on a particularly bad day, I might describe as “bulbous”). And that’s part of the reason, sure, but I can’t pretend it’s merely a visual preference of mine. As marked on Judgments, that particular sweet spot—far enough above the knee to be clear that it’s not a knee-length skirt, but low enough to be worn most places besides the Vatican—also marks a sweet spot for women’s comportment. Flirty shows you’re aware of your appeal but not taking advantage of it (mustn’t be cheeky!); flirty grants women the right to exercise what some might call “erotic capital” without being seen as, you know, a whore. Flirty lends its users a mantle of conventional femininity without most of femininity’s punishments; flirty marks a clear space of permission. Curtailed permission, yes, but sometimes a skirt’s gotta do what a skirt’s gotta do, right? So, no, it’s no accident that nearly all my dresses fall to this length. I wear “flirty” skirts in part because I play by the rules. I’ve never been good at operating in spaces where I don’t have permission to be.

Of course, that permission will change: The lines as shown on Judgments indicate not only hemlines and codes women are judged by, but where women are allowed to fall at any particular age. A “provocative” teenager might be slut-shamed, but she isn’t told to keep it to herself; a 58-year-old with the same hemline might well be told just that, if not in as many words. “Proper” isn’t necessarily a sly way of saying “frowsy” when spoken of a middle-aged woman, as it would be for a 22-year-old.

Given how widely this photo made the rounds, it’s clear it struck a nerve, and I’m wondering what that nerve is for other viewers, in relation to their personal lives—and personal wardrobes. Do you take this as commentary on rigid rules for women, or on the constant flux of expectations—or are those just two expressions of the same problem? Do you dress within “permission,” or do you take pleasure in disregarding permission altogether? Or...?

Tizz Wall, Domme, Oakland, California

On Looking the Part

I’m very aware of my looks, specifically as a sex worker. Personally, I’ve wondered if I’m attractive enough—I can get very self-conscious. I feel confident in myself, and I did when I first started too, but back then I was like, I’m definitely not the tall, thin, blonde, model-esque type, and obviously you have to be that to be in this line of work, right? So I wasn’t sure I’d get hired. Then, it’s funny—being there, there’s kind of a transformation that happens. So it’s particularly interesting to see the getting-ready process in the morning, because everybody is gorgeous—and the particular house I work in has a wide variety of body types and ethnicities and different types of beauty, it’s really varied—but you see everybody show up in their normal-person outfits, and then you see them do all this and it’s a whole transformation that happens.

I had no idea what this world was like when I got into it. I remember asking, “How much makeup should I put on?” My boss said, “Whatever is going to make you feel comfortable and make you feel like you’re going to personify this character”—which is an extension of yourself but also still a character. You’re kind of amplifying a certain part of your personality. Whatever will make you feel like that character, that’s how much makeup you need to put on.

On Bodily Labor

You show off your body in a certain way. One of women has lost a ton of weight since she began working, and that has helped her get more work. I know I’ll get more work if I do certain things that are more traditionally feminine. It becomes a business decision. There are definitely sex workers who don’t cater to that. But our particular community, the particular house that I’m in, that’s something the person running it gears toward. That’s what our advertising is geared toward. So that regulates a lot of our choices for our physical presentation.

I’ve actually gained weight since starting this work; when I first started I was doing roller derby, skating 10 to 12 hours week, and I’m not anymore. So now when I’m not getting work, I’ll be like, Oh my god, is this because I’ve gained weight? And I know that’s not it—I mean, I fluctuated just one size, it’s not this massive difference. But this feeling of the possibility that my looks are tied to my income can really hurt my self-esteem. Being financially independent is really important to me. In this work, everybody has slow weeks, and then you’ll get a rush with lots of work; it’s a back-and-forth. But when that happens, I can start to think that I’m actually putting myself at risk by gaining weight. Rationally I know that’s not the case—even if I were a supermodel, there would be an ebb and flow no matter what I do. But when I gain weight it’s more than just, “Oh, I’m having a bad day and feel so ugly and bloated.” Body stuff takes on a different tone. It’s less destructive in my personal relationships and my personal interactions and personal self-esteem, but with this financial angle there’s this feeling of, If I don’t lose this weight, I’m not going to work again.

On Being Seen—or Not

Clients will often request that I have them only look at me when I give permission. I mean, that’s very submissive! In a playspace, not making eye contact can represent submission and reverence. It can become about asking for permission, or earning that privilege in some way. If a client is coming to see a domme rather than going to a strip club or going to see an escort, they’re going to a domme for a reason. They’re seeking out that dominance. Saying “Don’t look at me” is a subtle, effective way of establishing dominance, of making it clear that this is my room, this is my space, and you need to respect that.

That applies outside of work in some ways—not to that extreme, of course, but in terms of self-presentation. It makes the argument of how you present yourself in a certain way to control how people look at you in a fair or appropriate way where you have some degree of control over it. Women are so judged by their appearance that making certain choices about how I present myself becomes a way of controlling how people view me.

On Commanding Attention

It’s amazing what can happen once you stop having the expected male-female interaction, since women are so socialized to be nice and really cater to men—even if you’re a staunch feminist, even if you’re really mouthy, like myself, before this job. I still have some of that tendency to apologize profusely if something goes wrong. I’m gonna be like, “I’m so sorry, I messed it up, I’m so sorry.” But I think having this job made me really realize the power I can have over a situation. I mean, personal accountability is important, and you should apologize when you mess up. It’s a matter of not overdoing it, not feeling really bad about it. Something went wrong? It’s fine, we’re moving on. Having that sort of presentation has a lot of power.

Doing the “I’m pretty but I have no brains” thing is not my goal. I don’t present that way, even as a sex worker when I’m trying to appeal to that male attraction, even though the presentation is definitely vampy and really conventionally feminine. And we definitely have clients who come in and think we must be stupid. My goal is that my presentation will command your attention—but now that I’ve got your attention I’m going to use all the other things in my arsenal. My brain, my sense of humor, being okay with myself and with what happens in that situation, communication skills. That definitely crossed over into dating: I’m going to use a certain presentation, and it will command your attention, but the other things are what’s going to hold it together.

Yer Cheatin' Heart: The Relationship Between Beauty and Betrayal

Looking at appearance and infidelity vis-à-vis the Petraeus household made me curious about what role beauty actually does play in betrayal. Most of us know from casual observation that it’s fully possible for a person to cheat with someone who isn’t as physically attractive as that person’s primary partner—but is there any sort of pattern there? Are people likelier to cheat with someone who’s conventionally better-looking than one’s partner?

I was surprised/relieved to find that there weren’t any studies available that delved into that particular question. (Not sure how that would work in a lab setting anyway: “Please send photo of mistress to...”?) But there’s a wealth of research looking at other intersections of appearance and infidelity. Some of the more interesting findings:

1) Women reported feeling more threatened when “the other woman” was particularly attractive—but only in cases of emotional infidelity. In sexual infidelity, the other woman’s appearance had no effect on the wife/girlfriend’s feelings about the betrayal.

I was surprised by the findings of this study at first. On the surface, our culture tends to equate beauty with sex appeal more than it connects beauty and lovability. (The frowsy girl in movies never gets laid, but someone’s gonna see her heart of gold, right?) So wouldn’t a woman feel more threatened by an attractive rival when the betrayal was sexual more than emotional?

But with a closer look, it makes perfect sense. Sexual infidelity can be as meaningless as a drunken, regrettable one-night stand; emotional infidelity implies not a fleeting crush but something with a deeper current that develops over time. In other words: Someone cheating sexually could just want one specific part of a person (ahem)—but someone cheating emotionally is entranced with the entirety of the third party. And in a culture that likes to make-believe that a woman’s value as a person lies in her beauty and feminine charms, it’s logical that a beautiful woman—i.e. a valuable woman—is going to pose a greater threat in situations of emotional infidelity. When your partner becomes emotionally invested in another person, it stings regardless of who that person is. But when it’s someone whose value is evident, the threat is greater because your own value diminishes comparatively. With sexual infidelity, the value of the person isn’t called into question as sharply as it with emotional infidelity, so a beautiful “rival” poses less of a threat.

2) Women are more likely than men to end a marriage after their own infidelity—and the more attractive the woman as compared to her husband, the likelier she is to do so.

To put it plainly, attractive women are likelier than men to use infidelity as an opportunity to “trade up,” in the language of this study. The lesson here seems clear: Beauty increases a woman’s “market value,” while infidelity (including the person’s own infidelity) lessens the value an individual gets from her or his partner. Put the two together and it’s not hard to see how a woman might feel as though the algorithm of the relationship has changed after infidelity, to the point where ending the relationship makes sense in a way that it might not if she weren’t confident of her “market value.” By the way, I’m putting that in quotes because it makes me a little queasy not to.

3) Women were twice as likely as men to endorse “the other person makes me feel attractive” as an acceptable reason for infidelity.

Endorse is a strong word here but it’s the word used in the study so I’m borrowing it here; the participants weren’t necessarily saying infidelity was hunky-dory under any circumstance. With that weakened use of endorse in mind, take this in: 20% of men endorsed cheating if the other person made them feel attractive, while 42% of women said the same. In addition, women were 6% likelier to endorse infidelity when the cheating party wasn’t attracted to their spouse. (In fact, the only reason for cheating that men endorsed significantly more than women was “Opportunity presented itself,” with 32% of men signing on.)

Read cynically, this confirms the wretched stereotype of women as hopelessly vain, forever needing to be fawned over and then getting huffy enough to cheat if that fawning stops. But I interpret this rather as a sad comment on what all these studies are driving at: Plenty of women still internalize their value as lying in their looks. Feeling beautiful under someone else’s gaze can be intoxicating—and so validating that it might trump other values one might hold dear. Bathing in that gaze is often construed as such a foundational condition of a relationship that it might be easy for some women to quietly substitute in that feeling for commitment and fidelity. Indeed, so much advice given to women about how to “catch his eye” is geared toward maximizing physical attractiveness that if you squint hard enough, catching his eye can appear to be the grand prize that women are supposed to shoot for—not the relationship itself. Little wonder that under that paradigm, plenty of women might be willing to excuse infidelity with “but he makes me feel beautiful.” Plus, since attractiveness is often seen as the way one “earns” sex (only the beautiful get to do the nasty, you know), it makes sense that having your appearance highly valued by another lays the groundwork for beauty’s payoff.

4) Men married to women they believe to have a high infidelity risk are likelier than other men to use “mate retention tactics” to keep their wives from straying. Women, on the other hand, were no more or less likely to deploy such tactics regardless of whether they thought their husbands might cheat.

You’ve gotta love these “tactics” too: punishing the woman for whatever it is that makes him think she might stray, putting down competitors, submission and debasement, and “concealment of mate,” whatever that means (the study didn’t say). Of course, that’s better than the tactics used by men who perceive their wives to be more attractive than they themselves are: emotional manipulation, derogation, sexual threats, and violence against rivals. And once again, women who perceived their husbands to be more attractive than they themselves are weren’t more likely to use those tactics.

These tidbits are just randomly dispiriting until you look at another finding of the study and see exactly how dispiriting it really is: There was no correlation between how hot a guy thinks his wife is and how likely he thinks she is to cheat on him. Yet a woman’s perceived beauty and her perceived risk of infidelity are not only punished, but are punished in much the same way. (Not all the “mate retention tactics” measured in the survey were negative ones; love and care were considered tactics, for example.) So basically: Women are groomed to maximize their attractiveness, in part because that’s supposed to snag you a higher-quality mate. Yet getting into a relationship with a man who thinks you’re better-looking than he thinks he is carries risk. Talk about feeling cheated, eh?

These findings are hardly conclusive, largely because some of them relied upon hypothetical infidelities, and also because the conclusions drawn from the studies are rather oblique. (Plus, I’m skeptical of beauty studies to begin with.) Intellectually, what I gather from them is what popped up plenty of times above: As long as we see women’s value as lying largely in their appearance, there will be a relationship between beauty and betrayal, even if that relationship isn’t as straightforward as some people would make it seem.

Personally, though, I take something else from this data: Since there’s no pattern here as far as actual behavior, there’s little use fretting about one’s own appearance in conjunction with infidelity. I know that when I’ve been cheated on, my instinct (after seething rage) is to wonder why I alone wasn’t enough for my partner. And, yes, to wonder whether the betrayal happened because I ceased to be attractive in the cheater’s eyes. (I didn’t say it was a healthy instinct, people.) But looking at all these studies, they’re...fuzzy. Weird little conclusions come up, none of which explain the only thing I’ve really cared about when I’ve been betrayed—or, for that matter, when I’ve had the poor judgment to betray a partner myself: Why. The why of betrayal sears and smolders, and at least in my case, it never fully burns out, even years later. I don’t feel anger when I think of my high school boyfriend telling me he kissed his ex during a snowball fight, but the why still flickers, even if the only emotion it provokes in me is nostalgia for the time when that was the most complicated thing I could imagine happening in my intimate life.

These studies don’t provide a why. And as satisfying as it would be to have something concrete we could turn to in times of the heartbreak of betrayal, it’s fitting that no why emerges. Can we ever know why? If “opportunity presented itself” is one of the more popular reasons for cheating, there really isn’t a why. It might be cold comfort to see that beauty isn’t really a part of the why—or it might not be comfort at all, depending upon your relationship with beauty, and with infidelity, for that matter. But only when we learn to take our own perspective on appearance out of the equation can we begin to see “opportunity,” disappointment, and the chaos of love and desire—the unsatisfying but undeniable components that are likely a part of the why—as the real flame-throwers here.

This is part two of a three-part series on appearance and infidelity. Part one is here; look for part three next week.

The Petraeus Affair: Infidelity, Beauty, and Scapegoating

The sex lives of public figures bore me. Rather, the sex lives of public figures interest me no more than that of, say, my dentist. My view on sex is generally pretty solipsistic: If it’s not me having the sex in question, I don’t particularly care about it, and I don’t understand why anyone besides those directly affected would.

So I didn’t pay much attention to the David Petraeus scandal—at least, not until I read this excellent piece by Meghan Daum that questions the mandate of beauty in high-profile women. The article draws upon Petraeus’s wife, Holly, and the flurry of nasty comments in the “chattersphere” about how one could hardly blame Petraeus for sleeping with his attractive biographer, given that Mrs. Petraeus dared to look like a middle-aged woman who doesn’t pay homage to the beauty industry at every opportunity. "If it's no longer shocking that a powerful man would have an affair with a younger, worshipful woman,” writes Daum, “it is a little shocking that the wife of that powerful man, nerdish as he is, would thwart the beauty industrial complex quite so vigorously.”

Daum’s larger point—that we need to eliminate the double standard dictating that accomplished women like Olympia Snowe, Dianne Feinstein, and Nancy Pelosi must pay attention to conventional beauty standards while their male counterparts can eschew them—is one that needs to be made, repeatedly, until things change. (Remember the hubbub when Hillary Clinton had the audacity to speak at a news conference without makeup?) But what’s interesting to me is something Daum acknowledges in her article: Save for a smattering of comments-section trolls, nobody is publicly suggesting that Holly Petraeus’s low-key, glamour-free looks are to blame for Petraeus’s infidelity. Yet the piece hinged upon that very idea, and the piece gained traction because we all quietly understand the game of pin-the-blame-on-the-gray-haired-woman. Save for an ugly little post from Mediabistro, a bizarro article about how all the women involved in the scandal could use a makeover, and the aforementioned comment-section trolls, the only mention of Holly Petraeus’s looks I could find by poking around online comes from...well, Meghan Daum, and people rightfully echoing her point. Few people are trying to suggest that Holly Petraeus’s gray hair is responsible for her husband’s dick falling into another woman—but we get the idea anyway, even when it’s not spoken aloud.

If we’re collectively too kind to snark at a pained woman who has been publicly humiliated, we’re not above raising our eyebrows when the betrayed wife is conventionally beautiful. “If Tiger Woods could cheat on Swedish model Elin Nordegren, what chance do other women have?” cried the Examiner. “Beauties and the beasts,” blared the New York Post after Tony Parker cheated on Eva Longoria. There’s a certain freedom to say it when a beautiful woman has been betrayed, because we’re ostensibly championing the woman; we’re reassuring her that the dude must be cray-cray to cheat on her, because she’s hot, and it’s too bad that her insurance policy of being good-looking had a loophole for infidelity. A loophole that an estimated 22% of married men have exploited at some point, sure, but never mind the 1-in-4 odds at play, right? Those odds are “supposed” to fall in the favor of the Eva Longorias of the world—at the expense of the Holly Petraeuses—and though both parties gain our sympathy, only one of them garners a head-scratching “huh?”

There are all sorts of problems with that mind-set, starting with the insulting idea that good looks are all that wives can count on to keep their husbands faithful (note that while plenty of pieces on Holly Petraeus highlight her striking accomplishments on behalf of military families, none of them suggest her husbands is nutso for cheating on her because of those accomplishments). But deconstructing the idea doesn’t answer the fundamental question of why we’re so eager to tie appearance to infidelity.

I can’t help but think that maybe we want beauty and cheating to be linked. Because if they’re not, the statistics on infidelity are just too depressing. I remember confiding in a friend after a man I loved cheated on me. She was sympathetic, but a part of her response continues to flit around in my mind years after the fact: That’s just how men are, she said. She wasn’t trying to say it was “natural,” but rather that in her experience, men were simply eager to cheat, so I couldn’t take it personally. Let’s say for a moment that she was right—that men just cheat, end of story. It’s awful to think that a man might cheat on you because someone more attractive came along. But it’s worse to think that he cheated just because. Because then the logical fallout is that since he cheated just because, every man cheats, so you’d better learn to either adopt a laissez-faire attitude about the whole thing or get used to losing your dignity on a regular basis, because this is just how it’s going to be.

Accepting that notion would undermine the entire idea of monogamy, which, in this culture, is how we construe commitment. So we refuse it, and we seek a scapegoat for infidelity—and what better scapegoat than something that has already instilled in plenty of people a sense of insecurity, futility, and self-abasement? Beauty, along with its surrounding pressures and expectations, comes in mighty handy here. It makes me think about how often beauty and appearance are used as a scapegoat for other issues, and indeed how rigid we are with the narrative arc of women’s relationship with our looks (woman feels bad about body, woman works to come to peace with it, all is well—which is a fine tale, except it sets an expectation that women are displeased with their bodies, leaving little room for those who might not fall prey to that narrative).

It’s not often that I’m going to argue in this space that beauty is irrelevant; the entire thesis of this blog is that personal appearance becomes relevant to pretty much everything. And that’s not what I’m arguing, not exactly, not least because none of us have any way of knowing exactly why David Petraeus slept with Paula Broadwell—or why any person, anywhere, has cheated on someone they’re ostensibly committed to. (It’s something you often hear from philanderers themselves: I don’t know why I did it, I don’t know what came over me, The whole thing was stupid.) But I will argue that beauty is more relevant to the discussion of infidelity, and to how we make sense of infidelity, than it ever is to infidelity itself, which is why, as Daum points out, “assiduous gym rats with nary a gray hair get cheated on.”

In fact, there’s further evidence of this in the Petraeus case: Since I only paid cursory attention to the story yet kept seeing photos of Jill Kelley everywhere, I assumed that she was Petraeus’s lover. It actually wasn’t until I started researching this piece that I saw a picture of Broadwell, his actual paramour. As a long-haired Lebanese-American socialite usually photographed in bright, tailored dresses, Kelley has more photogenic glamour than an academic from Bismarck who favors a severe hairstyle. Bluntly put, Kelley looks the part of the stereotypical homewrecker more than Broadwell does—which is, I’m guessing, a large part of why her visage, not Broadwell’s, has become one of the iconic images burned into the public mind in regards to this affair. We want a fall gal, and Kelley makes a good one (especially given that she committed adultery as well, just not with the main figure involved here).

The sooner we stop gaping, wide-eyed, when we see men have affairs behind the backs of their beautiful wives, the sooner we can truly start leaving the low-maintenance betrayed wives like Holly Petraeus alone. And the sooner we can do both of those things, maybe we’ll come just a hair closer to understanding why we place such importance on an institution so many people flout—with lovers beautiful and plain, glamorous and mousy, younger and older. Perhaps with practice we’ll even come a little closer to fixing it.

Beauty Privilege: Can We Talk?

Illustration by Steph Becker

Just like me—in fact, just like pretty much every woman who has ever written about beauty in a public forum—the coauthors of Beauty Redefined have been critiqued as being both A) too pretty to understand the challenges surrounding looks bias, and B) so unpretty that it's no wonder they're writing about body image and self-esteem issues, the poor jealous things. What's that I hear you saying? Something along the lines of: But those statements are totally contradictory? Why yes, they are. That is, they're contradictory in their sentiment, but they're identical in their value, which is: Whatever this woman—or any woman—is saying about appearance must be evaluated by her own beauty, or lack thereof.

Lindsay and Lexie at Beauty Redefined have some excellent talking points at their post on this matter, and if I could cosign the entry, I would. Their entry also got me thinking about one of the more elusive aspects of beauty privilege and looksism, which is: It’s really difficult to talk about.

I mean, we can talk about beauty privilege—or negative beauty bias—in the abstract, and we can talk about things we witness. But you think it's difficult to prove something like the subtler forms of ageism or racism or sexism? Try just discussing looksism. Not only is looksism even more amorphous than plenty of other "isms," but think of how you sound if you talk about it openly: It can seem hopelessly narcissistic to own up to one's "beauty privilege," and hopelessly affirmation-seeking to talk about suffering at the hands of looksism. Unlike privilege that comes from being white, able-bodied, male, thin—and even, to a lesser degree, being heterosexual or middle class—beauty privilege is something that's both physically evident and seemingly impossible to deconstruct from a personal point of view, which is a key way that privilege (and lack thereof) comes to be understood and taken seriously.

I'm guessing that as a woman who is nominally attractive but in no immediate danger of launching a thousand ships, I've received some benefits from looking the way I do but have been spared both the grander forms of beauty privilege (I'm fairly certain I've never been hired as set decoration) and the major drawbacks of beauty (nobody assumes I’ve coasted by on my looks). But here's the thing: I'll never really know to what degree I've experienced beauty bias, in either direction. Few of us do. It could be that the small perks I've been attributing to being a nice-enough-looking lady—say, getting slipped a free cookie now and then at the deli—are just people being kind, and that they'd do the same if I were homely, or a man. I'm sure that is indeed the case sometimes, but I've been smacked down by my own naivete in this regard enough times to know better than to get all Pollyanna here. (One of the free-cookie men suddenly stopped giving me cookies after I stopped by once with a male friend. It was the illusion of availability that he liked—and once that fell to the wayside, so did my supply of white chocolate-macadamia treats.) We can have our hunches, but for the most part that's all we have.

I think of the "click" moments I've heard time and time again of women discovering, without a doubt, that they were feminists; much of the time it's an instant recognition of and reaction to sexism. I'm left wondering what sort of "click" moment it would take for a woman to discover, without a doubt, that she was receiving or being denied a form of beauty privilege. Receiving privilege is particularly difficult to tease out, in part because privilege functions by being unspoken, and unrecognized. (Sitting at the front of the Montgomery city bus in 1954 wasn't what we'd now term "white privilege"; it was the law. Beauty privilege may be encoded in a handful of circumstances, but for the most part it's not.) And since looks are painted as being an ineffable part of a woman's essence—particularly in the case of women considered conventionally beautiful—it becomes even murkier than other forms of privilege. How can you have a "click" moment about something that's supposedly transcendent?

I don't write a lot about beauty privilege, and this isn't the only reason why (mostly I just feel like there are more interesting things to write about). But yes, it's a reason. Not only is there a fear of being called a narcissist if I write about whatever forms of privilege I might have experienced, there's a fear of being called delusional if any given critic doesn't find me...privilege-worthy, shall we say. Maybe this fear is rooted in my personal reality of being an attractive-enough but not stunning woman. Or maybe it's rooted in the reality of being a woman, period. (And, as it happens, I've been called both a narcissist and delusional just for writing about appearance at all, so there you have it.) As much as women are punished for not measuring up to some amorphous beauty standard, we're punished just as much for thinking we're "all that."

“When we dismiss someone’s words due to our assessment of their appearance, we’re minimizing them to their body,” write Lindsay and Lexie at Beauty Redefined. That’s absolutely true, yes. Yet unlike Beauty Redefined, a good portion of The Beheld is expressly written from a first-person perspective. Much as I’d like my words to speak for themselves, I can’t say it’s necessarily wrong to take the looks of people writing personal essays about appearance into account when reading their work. My experience of beauty is undoubtedly different than, say, Charlize Theron's, just as Charlize Theron's experience is beauty is different than it would be if she wore her Monster look 24/7. Readers who assume after looking at a photo of me that they know something unwritten about my perspective might not be entirely wrong—but as the disparate evaluations of my looks from various commenters has shown, they can't all be "right."

We’re so used to viewing women as objects (I include women in this) that we may forget they are subjects too, particularly when discussing looks. Most of the time we talk about beauty, we understandably talk about it in terms of how we look at people, not about the subjective experience of looking beautiful, or plain/cute/weird/misshapen/hot/ whatever. Certainly we don’t usually talk about it in terms of how we believe we’re seen. And if we want to understand the labyrinth of beauty in a richer manner, that might be the most revealing perspective of all.

Invited Post: Pretty/Funny

Finke knew what she was doing; hits for her piece would go up by declaring something so controversial. And she’s already had responses with people ranting about her and posting photos of funny women, talking about what a fool she is. That’s all great and helpful. My response is that I’ve never understood why the funny vs. beautiful dichotomy even exists—and I’m questioning how we created a world in which it does. (Okay, and also that Brooke Shields is hilarious. When I saw her on Friends as the obsessed soap opera fan, I thought, “Yes, Brooke! You went from underwear model to blasé movie actress to Norma Desmond! You will not let people tell you who are!” Only someone who is unwilling to let herself grow would look at Brooke Shields and decide that a woman who used to parade around in her panties for a living can’t decide to start letting her wit do the dazzling…while still looking movie-star perfect.)

Beauty is mesmerizing, transportive; it makes tongues wag and it makes times slow down. Beauty says, “I am here as an object for you to admire,” and while it contains power, it’s a power that turns its owner into an object of projection and fantasy. Comedy is refreshing, jarring, true, smart. Comedy says, “I am powerful, in a way that means I am going to call it like I see it, and sometimes you will feel taken aback.” The ability to deliver a comedic line is a form of confidence that a person has—or doesn’t have. The ability to show up at an event and know that a certain percentage of people will stare at you is a confidence a person has, or doesn’t have. The difference is that beauty, though a quality that dazzles a room, invites people to make up who you are and fill in the blanks; comedy shuts that down. When a beautiful woman demonstrates a sense of humor, it goes one step past showing she’s smart and gets right to, “I’m not just smart, I’m questioning and I’m making observations. I am an active participant, not a shell.”

The idea that a woman can only be funny if she has suffered is an interesting one, for humor can be a sign that someone is able to find happiness at all times, and it is often developed as a survival mechanism for those dealing with hard times. But the implication—and this is not just Finke, it’s the reason she and others have this issue in the first place—is that beautiful people don’t have everyday problems and therefore can only be funny if they’ve suffered the plight of the underdog. What’s particularly disturbing about this implication is that a beautiful, funny person has to keep proving their pain—has to keep apologizing. “I’m still hurting! I’m not just enjoying being funny and beautiful! I hope that makes you feel better about your sucky life and limitations!” Why do we need to know that Tina Fey wasn’t attractive when she was younger? Why did Joan Rivers constantly make fun of her own appearance, then pick relentlessly on gorgeous Liz Taylor when Liz was struggling with her weight, and then resort to frightening plastic surgery? Do we need to see a funny, successful woman apologizing constantly for her wit and success in order to feel that all is right with the world? Must every beautiful funny woman pull out “awkward teenage photos” to prove “but I’m one of you! Really!”

The beautiful vs. funny issue comes down to the recurring problem of women not being allowed to embrace all forms of their power. A beautiful woman, out of politeness, has to pretend she doesn’t notice she is being watched, even though of course she should be aware of it, for reasons ranging from self-protection to understanding why she might receive special treatment, either preferential or jealous. A funny woman proves consistently that she is aware of herself in the world, and is insightful about human behavior and motivation—and when this is combined with prettiness, it leads to a viewer wondering, “Wait, so are you aware that each hair toss drives people wild too? How much of this are you picking up on?”

The division between beauty and humor hasn’t always been as sharp as it is now, and throughout film history there have been women who have shimmied through the cracks. On the late ‘80s/early ‘90s hit Designing Women, a rare woman-focused show where attractive ladies were not trying to cut each other’s throats for men—though they all did date and had some lasting relationships—beauties Dixie Carter and Delta Burke both owned their physical beauty and their comedic strengths. In The House Bunny and Legally Blonde, Anna Faris and Reese Witherspoon, respectively, win our hearts as women who discover that underneath their pretty exteriors they really are smart…and they are hilarious doing so. But the shining era of beautiful, glamorous, hilarious women in film was the 1930s. Myrna Loy, Constance Bennett, Carole Lombard, Jean Harlow, Kay Francis—heck, just watch The Women (the 1939 original, please) and you’ll see why I get so frustrated with how far we’ve regressed from when a film like this allowed each lady to shine.

So what changed? The foundational problem some members of our culture, like Finke, have with funny, pretty women is that they’re just too much of a threat—and in 1939, most women weren’t really seen as threatening in the least. Carole Lombard could be beautiful and hilarious in 1936’s My Man Godfrey because the biggest threat her dizzy socialite character could possibly pose would be selecting the wrong “protégé.” Fifty years later, women had gained in status, income, and independence—so quick, call off the funny ladies! You can see the unimaginative screenwriter’s dilemma: “Wait, she dazzles me and I project my fantasies onto her, but she also sees the world in a way that shows an ability to question everyday behavior and call bulls**t when she sees it. Should I objectify her, or go to her for wisdom? Can’t she make this easier for me?”

I’ve dealt with a rare type of snarky man who can’t laugh at a woman’s joke, and I smell it right off. I see humor as play; I see it as a way to connect, to loosen the atmosphere, and most men respond to this. But there are exceptions. When I was 20, I worked at a food counter in the stock market. All the men were sweet and friendly to me, but there was this one smarmy fellow who would never laugh at my jokes. My delivery is sweet and friendly, and occasionally dry, but I’m never trying to be “one of the guys.” When I delivered the food, I would banter, and the men would banter back, and it was fun. But this one fellow just couldn’t laugh, because I was a cute girl in his age group and therefore my purpose was to be an object he could look at as powerless. He would look at me in the sleaze way, but my jokes were not welcome. One day, I’d had it up to here with him. So when I showed him the day’s menu and he said to me, “Is the fish fresh?” all I could think was, He’s toast. So I put my hand on my hip and said, “Yeah, I shot it this morning.” Dude was so shocked that he burst out laughing, and I walked away thinking, “That’s right. Who’s your daddy now?” But it was only because I was finally saying, “Enough already—you’re going to deal with it,” that I broke him out of his attempt to make me feel that my attempts at showing smarts were unwelcome.

I currently write and star in a web and film series called The Sisters Plotz, featuring Eve Plumb and Lisa Hammer. We style ourselves in a vintage, feminine way with an indulgent dose of camp-glamour. Eve and Lisa are two seriously pretty women. Am I about to tell them to disempower themselves by perhaps wearing less flattering outfits or messing up their hair a little bit because I’m trying to decide if they should be funny or pretty? Maybe we should all make jokes pretending we think we’re fat or we should pick on some part of our face or body, because that will make people love us? Um, no. Right now I want to live the dreams I had when I was growing up. This is the one chance I get to be in the world, and I understand that there will always be acts of cruelty or even just idiocy that I don’t understand. But I want to live in a world where women are allowed to be funny and pretty and smart and free and strong and glamorous all at the same time—or none of these things if they don’t want to be—and I know that there will always be people who just don’t agree that I’m allowed to enjoy this type of privilege. But that’s all right. My red lipstick and I are ready.

__________________________________________________________________

Lisa Ferber paints and writes witty character portraits influenced by her fascination with humanity. Her works display an appreciation of the beauty and quirks of human behavior, as well as a compassion for its foibles. Her paintings have shown at National Arts Club, Mayson Gallery and other venues, and sell to private collectors. Her films have screened at the Tribeca Grand and the Bluestocking Film Series, and her film "Whimsellica's Grand Inheritance" won the People's Choice Award at the "It Came From Kuchar" festival. Her plays have been performed at notable theaters such as LaMama, DR2 Lounge/Daryl Roth Theatre, and her play "Bonbons for Breakfast" was a New York magazine "notable production." To learn more about her projects, please visit LisaFerber.com

Edith Wharton and Yo Momma

according to Jonathan Franzen, Great Observer of The Human Condition

I'll be posting actual content this week, but for today I'm just getting into the swing of things, so here's my warmup: For only two dollars—yes, two American dollars!—a month, you can get a subscription to the digital magazine from The New Inquiry, a journal of thought and criticism where I'm proud to syndicate The Beheld. This month's theme? Beauty. I was enlisted to play the role of co-editor this issue, in part because several of my favorite interviews have been repurposed, and in part because it features my response to Jonathan Franzen's assertion in The New Yorker that Edith Wharton's lack of physical beauty was one of the few things making her sympathetic.

Beauty shop opens at Cornton Vale women's prison. "Prison officer Carol Maltman had the idea for the shop after asking prisoners what kind of products would make their lives behind bars more bearable. She was hit with a staggering 1444 suggestions – every one of them relating to cosmetics or toiletries."

Bin Laden dyed his hair!

Burt Reynolds' 40th anniversary of appearing nude in Cosmo. Am saddened to learn that bearskin rug was intended to be ironic.

Slate asks if ladymags' insistence on featuring celebrity body woes from women who already fit the beauty ideal is helpful. I waver on this: I think it actually can be a useful stopgap measure, but its effects should be short-term. Seeing someone who looks media-perfect say that they struggle in the same ways I do is a reinforcement that absolutely fucking nobody fits that level of perfection—but as the Slate piece points out, it also provokes the question of, "My god, if she describes herself as hippy, what am I?"

What's up with Beyonce's whole earth mother thing? Bim Adewunmi looks at "fake authenticity."

Did the public persona of "Black Dahlia," the victim of a highly sensationalized (and highly gruesome) 1947 murder case, begin before her death? Crime historian Joan Renner—who happens to run a vintage cosmetics blog—thinks so, and it's because of her makeup. (Thanks to Sarah Nicole Prickett for the tipoff.)

She rarely writes about beauty so I never have a chance to include her here, but I've gotta give a random shoutout to ModernSauce, the only design-ish blog I read, which I do because the writing makes me laugh out loud, which is potentially hazardous given that I'm often eating graham crackers when I'm reading, and I live alone, and could choke and die and nobody would find me. But despite the hazards, it's so sly and offhandedly insightful, I read on. I read on.

Rebekah gives what might serve as an epilogue for the body hair discussion that took place here a few weeks ago, showing exactly how complex of an issue it is.

Gala Darling's riveting, exploratory, searingly honest piece on self-harm is a must-read for anyone who knows someone who has self-harming behaviors (like cutting). Without glamourizing self-harm in the least, she shows the ambiguities of what it gives its sufferers: "The majority of women who wrote in were not embarrassed by the remnants from their days of self-harm, but instead saw their scars as an integral part of who they are; part of the journey towards loving themselves entirely. In fact, some women were almost proud of their scars, choosing to view them as proof that they could overcome something horrendous & go on to not only survive, but thrive."

The Blind Hem continues the discussion on modesty fashion blogging, this time from a modesty blogger, penned as a response to their earlier piece on the matter, which took a more skeptical view of modesty blogging claims.

An excellent trio of questions from an excellent trio of bloggers: Does your clothing fight your body? Do you wear more makeup when you're down—or, for that matter, up? And what does it mean to "try too hard"?

Modeling as Modern-Day Physiognomy

pub. 1889, Crackpot Press

The features of my own that I suspect make my face appear friendly don’t necessarily correspond with how a physiognomist would classify me (the shape of my eyes indicates “tenderness,” but the placement of my irises reveals that I’m “timid and phlegmatic,” so it’s a draw). But the ease with which strangers approach me—and the way I quickly deduce who I should ask for aid or directions when I need them—makes me think that plenty of us make our own amateur conclusions about what faces mean. Still, I’d love to zoom back to the 19th century and have my face read: The amateur scientist in me (okay, the kook in me) wants to “know” what my face means, even though I know full well it's more along the lines of astrology than even something as "scientific" as the Myers-Briggs personality test. (We ever-curious ENFP Geminis are always eager to learn.)