{For more long-form interviews from The Beheld, click here.}

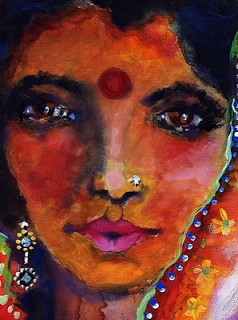

A highly productive bonne vivante, Lisa Ferber has shown her paintings and illustrations at National Arts Club, the Painting Center, and Village West gallery. She's also the creator, writer, and star of the feature film The Sisters Plotz (directed by Lisa Hammer, and starring Eve Plumb, Lisa Ferber and Lisa Hammer), which debuted at New York City's Anthology Film Archives in 2015, and launched as a Top Five Most-Watched video on FunnyorDie.com. Words like whimsy and satire are frequently applied to her work—but it’s her enchantment with beauty, expressed through vibrant color and markings of high glamour, that made me want to interview her. A featured speaker at New York University on independent arts marketing, her keen awareness of image extends beyond canvas and stage to her signature colorful wardrobe and polished presentation. We talked about makeup as a symbol of humility, the glamour of the absurd, and beauty as a marketing tool. In her own words:

Photo: Meryl Tihanyi

On Apologies

There are ways people have to deal with physical beauty that they don’t have to with other assets. Beautiful people are supposed to act as though they don’t know they’re beautiful, even if it’s kind of a fact. Somebody might say, “I’m good at math” and not apologize for it, but for a woman to say, “Yeah, you know, I’m really pretty”—nobody does that. It’s weird that people are modest about being beautiful because it’s sort of an accident. But it can be a way of stepping away from being threatening, since beautiful women are seen as threats. I remember complimenting this woman who was working on a show with my then-boyfriend. I said she was really pretty and she said, “It’s amazing what a good lipstick and a great dress can do.” It made me like her more because I felt she was saying, “I know I’m in a show with your boyfriend, but I am not a threat to you.” I felt she understood that sometimes women can be insecure about having a pretty woman around their guy, and that she could handle that with humility and manners without insulting herself.

Part of it is the social power women wield with beauty. When we say, “Oh, that woman is so beautiful,” we give her power and mystery. Beauty simultaneously gains someone social respect and people’s suspicion. Are there certain types of beauty that don’t incur the wrath of other women? Or certain levels of beauty? If you work with someone who has that California-girl kind of beauty, everyone is going to want to think she’s dumb, because she’s pretty in that certain type of way. Whereas I think women are into someone like Angelina Jolie because she’s freaky-looking but also really beautiful.

I think people believe they’re supposed to apologize for beauty because it’s genetic. Nobody’s allowed to show that they know it, yet most of us are also raised to present ourselves confidently. If you don’t groom yourself and make the effort, it looks as if you don’t care—or even that you’re conceited. I go through phases of not wearing makeup, and someone said to me once, “I noticed you don’t wear any makeup—how come?” I remember thinking, Why do I need to explain this? Is she saying that I don’t have the right to think that I look good without it? Should I wear makeup just to show that I don’t think I’m okay without it?

I think as much as women are raised to believe in ourselves, we’re also taught that a woman who’s prettier or slimmer than the people around her will be hated—think of the whole idea of “You’re so skinny, I hate you!” That mind-set can prevent women from revealing their full bloom. It’s really only been in the past few years that I’ve been able to not just present myself comedically, in terms of the way I look. For many years I felt like my self-presentation had to have something ridiculous about it, sort of kooky—and sure, there’s always going to be an artsiness about my style. But for me to just put on a beautiful dress and feel comfortable looking elegant and serious and poised, and not have to have something ridiculous about it—I had to be ready to say, “I can handle this.”

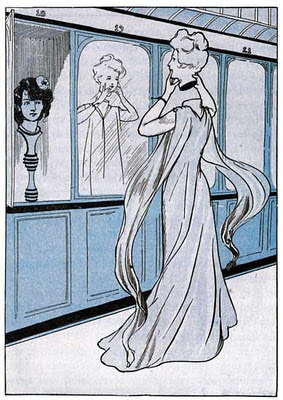

Djuna’s Croissant Had Failed Her

On the Glamour and Humor of Her Work

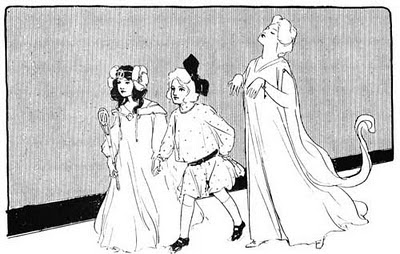

People have always responded to my work as witty, both my writing and my visual art. Only recently have I thought: You know, I really love beauty. I want my visual work to be transportive—to be beautiful as well as witty. Wit has a glamour to it, which I hope comes through in my work. I also think absurdity is glamorous, if you think of glamour as something indulgent and transcendent. Glamour means there’s a sense of mystery that makes you want to get closer, but you suspect that you can’t. So I put my women in makeup and necklaces—I’m not going to draw schlubs! But for somebody who loves beauty so much, I’m not painting a picture of the prettiest girl in the room. People tell me that I create characters, almost like pop art or illustrative art—they’re not supposed to look like people we know. But something can be beautiful even if it’s not realistic. I want that feeling of “Aaah” that comes because something is gorgeous, with beautiful colors.

When I’ve gone through tough times in life, the things that help me survive are beauty and humor, and it bothers me when people try to make them separate. Beauty and humor are both transportive—they’re magical. When I was growing up two of the women I admired were Lucille Ball and Gilda Radner, because they were pretty and funny. And one of my current heroines is Fran Drescher. She created a hilarious show and strutted around that set without apologizing for being beautiful, funny, and powerful. I think that women in comedy often make themselves less pretty because they’re taught they have to choose between pretty and funny. But I don’t want to have to choose one or the other in the way I present myself as a woman, or in my artwork. I want my viewer to enjoy two of my favorite things: beauty and humor.

Lady Ferber Gave Her Sommelier the Afternoon Off

On the Myth of the Underdog

We give ourselves credit for thinking someone who’s jolie-laide is cool-looking because she’s not conventional. But when you look at these women, it’s not as though they’re ugly—when Anjelica Huston walks into a room, everyone notices her. It’s like sometimes we’re taught to hate conventionally pretty things because we’re more feminist if we think weird-looking people are pretty—but those people are still pretty. I mean, Christie Brinkley is super-duper pretty. She’s the definition of pretty. But it’s not cool to say so because she’s conventional-looking. I love pretty! Pretty is great! I’m kind of on both sides of it. It upsets me that women are taught it’s imperative that they keep themselves looking attractive, but if somebody tells me I’m pretty, I think that’s nice of them. It annoys me when people think you have to choose one side.

Nobody relates to the pretty, popular character in a movie, even people who are pretty and popular. We’re always supposed to relate to the underdog. There’s this movie Boomerang, with Eddie Murphy—Robin Givens is the hot woman, and she’s evil, and Halle Berry is sort of the sporty underdog best friend. Halle Berry is the underdog! You’re supposed to relate to her, even though nobody can relate to Halle Berry! But the movie standards for beauty set us up, and maybe that’s for our ego—we get to feel like the underdog, but then we can think, “Wow, look at that underdog, she’s really beautiful.” And it’s because we’re convinced that we’re never the top thing. Certainly things like beauty contests don’t help. Beauty contests? That’s crazy!

I remember being an editorial assistant, and there was this other girl who worked there. I started to pick up on this vibe that she resented me somehow. I didn’t know if I was imagining things so I talked to a friend who had worked there for a while. He said, “Well, before you came, she was the only attractive young editorial assistant.” I hadn’t taken away anything from her—we were both young, pleasant women, but there’s this idea that there can only be one woman who occupies that space at any given time, and it becomes a part of our mentality. Take the idea of the 50 most beautiful people in the world—why should there be a competition? Men don’t think this way, and women don’t think this way about men. Women might compete for men, but the emphasis is on competing with one other, not on competing for him.

The Sisters Plotz premiere, 2015 (photo: Lisa Lambert)

On Beauty as a Marketing Tool

I think beauty is a fantastic marketing tool. By being beautiful, a person is saying that she has the things associated with beauty: health, wealth, success, all these things that we value. When you hear, “Oh, I ran into so-and-so, and she looked like hell,” boom—she’s leading an unhappy life. But when it’s “...and she looked great”—now, what that could mean is that she’s had a ton of Botox and has a personal trainer and is miserable. A beautiful woman can be miserable like anyone else. But we think she’s doing well.

Whenever we hear about the beautiful but tortured woman, we don’t really believe it, which is why we love it. We still think she’s cool in some way. The Jared Leto character on My So-Called Life was considered a heartthrob because he was beautiful and tortured. If he hadn’t been beautiful but was still tortured, his character would have just been some random guy, but to have a coating of beauty over an implied pain is perceived as intriguing.

As a visual artist, I am constantly expressing myself, so when I leave the house I’m going to be together. I’m going to have my lovely necklace, my lipstick, my pretty dress. There probably are industries where you have to play down any ornamentation in order to market yourself properly—but actually, when I’m presenting myself as a writer I try to be more glamorous. When you’re a writer people assume that you’re smart, and I don’t want to be seen as, Oh, she has brains, so she doesn’t have a body. I’m a body person as well as a mind person. When you’re a visual artist nobody necessarily assumes that you’re smart. So when an artist has something about them as a person that makes people want to keep looking at them, we’re intrigued by that and then want to know the artist’s work—which is part of marketing. Really, beauty is marketing: That’s the whole point, that you see somebody and they’re beautiful and you think, I want to get to know you. People are going to want to talk to a beautiful woman. Women are going to admire her, and men are going to want her, and she just seems happy and healthy and like she’s doing well. That’s what draws people in.

This works in other professions too: When I’m working in any job, I like to be valued as a part of the team, and part of it is showing up well-groomed, in nice colors, and just contributing to the overall atmosphere. I sang in choir when I was in Hebrew school—I wasn’t thinking about how my particular voice sounded, I just wanted to contribute to the beauty of the overall sound. It’s like that with my art, and my style. I want to be a pretty part of the world.

Henry Might Organize His Freezer This Evening

For sale inquiries, please contact Lisa Ferber at LadyFerber@gmail.com.

[This interview originally posted in March 2011.]