One of the questions we’ve frequently fielded here at World Hair Cup headquarters is that of women: Will there be a World Hair Cup for the FIFA Women’s World Cup in 2015? It would make sense, in some ways. Internationally speaking, women’s soccer still lags behind men’s in popularity and professional participation, but in the United States, that wasn’t true until fairly recently—until the dramatic surge of World Cup interest, I’m guessing that the names Abby Wambach, Hope Solo, Brandi Chastain, and Mia Hamm would’ve rang more bells in your average American household than Michael Bradley, Jermaine Jones, Mikkel Diskerud, and maybe even Clint Dempsey. And the iconic image of American soccer probably still remains a triumphant, shirtless Chastain kneeling in the throes of victory after winning the 1999 Women’s World Cup in a penalty shootout. Plus, given that the U.S. women’s team is internationally ranked far higher than the men’s team, it’s not unreasonable to think that at least in the States, popular interest in women’s soccer will mushroom now that men’s soccer has given it a nice nudge.

But will there be a women’s World Hair Cup? No. Why? Because the hair of women’s soccer is boring. It’s perfectly lovely; certainly female footballers don’t have bad hair. But a ballot for a women’s World Hair Cup would be little more than row after row of ponytails, with some braids and dreadlocks popping up, but nothing truly remarkable. Compare the actual "Group of Hair Death" ballot with a prospective ballot featuring those countries' female national players:

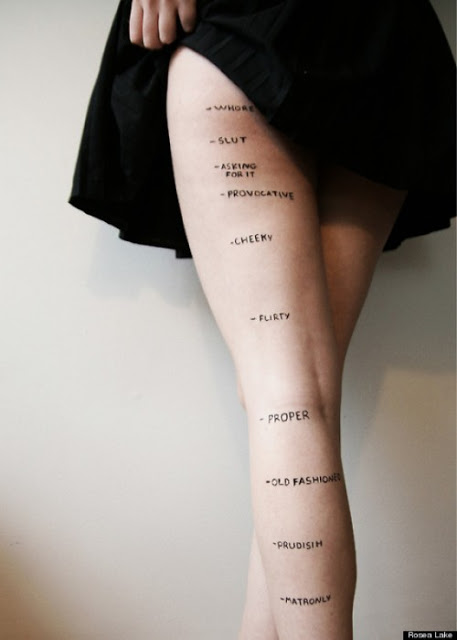

Why would this be, when, generally speaking, women are given far more leeway than men to visually ornament themselves? Why doesn’t Hope Solo have her jersey number shaved into the back of her head? Why doesn’t Abby Wambach ever fashion her ‘do into a spiky gelled mohawk? Why do so few—if any—African female footballers utilize hair bleach to set themselves apart like their male counterparts? Women’s appearance is more policed than men’s, but when it comes to hair, the range of acceptability is far broader for women than it is for men. Nobody thinks it’s unusual if a brunette lady goes blonde for a while. If it’s a dude, though—well, questions might well be asked about his sexuality. (In fact, questioning mainstream convention is exactly why some men dye their hair, as in the punk community.) Same with hair length: While long hair is still considered the default for women, a woman with short hair doesn’t get ridiculed for it, while a man with waist-length hair may as well change his name to Legolas. Logically, then, we should be seeing more remarkable hair among female soccer players, not less.

But we don’t, and here’s why: If you’re a male athlete, you’ve excelled at a crucial aspect of conventional masculinity. You’re stronger than other men, faster than other men, more coordinated than other men—you’re not the sissy who kept fumbling with the ball when playing catch with your dad. Nobody is going to question your masculinity. And if you’re a professional athlete, people will assume you’ve also nailed the “breadwinner” part of the masculine equation (even if that’s not the case). So you can do things like dye your hair between games, or have hair that trails down your back, or sport a fancifully bleached stripe, or hold back your flowing curls with a headband, and you are still quantifiably a dude.

Enter the ladies. Sports aren’t exactly considered unfeminine, at least in the States, in large part thanks to the skyrocketing sports participation of women and girls after passage of Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972. (Participation still isn’t equal, it’s worth noting.) But if you say the word athlete, most people will conjure up an image of a man. More to the point, there’s still a certain way to be a female athlete—namely, to adhere to codes of conventional femininity. I mean, there’s a reason I know who Anna Kournikova is, despite me not following tennis and her not having won major singles titles. Even if a female athlete manages to become a public figure without exploiting her sexuality—which many of them do—she still has to play by the rules. She has to be tasteful: She makes public appearances with light makeup that implies the healthy, wholesome, freshly scrubbed life she supposedly lives. She has neat hair, not so overly styled as to imply vanity but not so understyled as to appear sloppy. She’s extra good to make up for being competitive, because we all know women aren’t supposed to compete; if they do, they certainly don’t run and sweat and fight and bleed for it. Yet that’s what you do on the pitch—there’s no way around it—and so to compensate, a female soccer player has to demonstrate exactly how much of a “good girl” she is. Even if she hasn’t been acting like one.

There’s a twist here: sexual orientation. Sportswomen still have to fight the stereotype that they’re lesbians. That’s changing, both for straight athletes and gay ones (as evidenced by out athletes like Brittney Griner and Abby Wambach). But the longtime association of queerdom and sporty ladies means that many straight female athletes report the need to signal their heterosexuality—and what’s one of the easiest ways to do that? Look as conventionally ladylike as possible. Which means: Have longish, pretty, glistening hair. Which means: No World Hair Cup for women.

A note of irony: I’ve argued that by dint of being an athlete, sportsmen’s masculinity is protected, so they can do nutty stuff to their hair and it’s just, Oh, you boys. But so far, this hasn’t translated into a protected space of sexual orientation. I mean, it’s 2014 and there’s exactly one out player in the NFL, one in the NBA, one in the MLS, and none in the MLB. Many leagues have been taking administrative strides in support of gay athletes, and the shifting cultural landscape means we’ll probably be seeing more out players soon. But gay male players are subject to a stigma their female counterparts aren’t—Griner and Wambach both made news simply by being gay, but neither of them made the splash of Michael Sam’s drafting.

I’ve written a lot about the narrow spaces women are allowed to inhabit when it comes to their appearance: Be pretty but not threateningly so, care how you look but don’t be high-maintenance, etc. The World Cup—and, of course, the World Hair Cup (vote now! Tomorrow’s the last day to vote in the Round of 16!)—are a handy reminder that the highwire isn’t just for women. With the remarkable hair of the men’s World Cup players, one of the narrow spaces men live in is adeptly maneuvered, with everything from fluffy Afros to beard-mohawk combos to creative razor lines. It’s a construction of masculinity that has given these men a particular permission to sport the styles they do. But permission is something that can be withdrawn at whim. A right is not.