"Over a fancy lunch that costs more than we can pay for some articles, I explain how much we need his leadership... But, he says, Ms. readers are not our women. They're not interested in things like...blush. If they were, Ms. would be writing articles about them. ... He concedes that beauty features are often cococted more for advertisers than for readers. But Ms. isn't appropriate for his ads anyway. Why? Because Estee Lauder is selling 'a kept-woman mentality.' ... He knows his customers, and they would like to be kept women. That's why he will never advertise in Ms."

Vickie Dowling, Psy.D.,Clinical Psychologist, San Diego

Vickie Dowling specializes in helping her patients cope with the emotional effects of skin disorders. She’s uniquely qualified for the gig: A psoriasis patient since childhood, she developed her first debilitating full-body flare in college, a time when many young women’s self-esteem and body image are already in flux. A chronic, noncontagious autoimmune disease in which skin cells turn over more rapidly than normal, psoriasis’ physical effects include patches of dry, flaking skin and/or irritated patches. But it’s the emotional effects of psoriasis that made me want to talk with Vickie: Sufferers report heightened self-consciousness, frustration, embarrassment, and anger. And given the emphasis on women’s appearance, it’s no surprise that women with psoriasis report all these emotions in greater numbers than their male counterparts. We talked about focusing on our gifts, the loneliness of skin disorders, the power of education, and how to literally be comfortable in one’s own skin—a goal that people with and without skin disorders seek. In her own words:

On Her History

Being a teen brings vulnerability around self-image under normal circumstances—adding a chronic visible skin condition amplified my self-consciousness. Entering college, I pretty much had a good self-image—I liked my hair, I had a good figure, and I had good skin. I was pretty spoiled, so to speak, with how I looked, and I kind of took it for granted. I think a lot of us take a lot of things for granted until we have something stripped from us. I don't think I can "what-if" [to think how life may have been different without psoriasis]. I can't roll back.

Not only was my skin inflamed literally from head to toe, I also lost most of my hair. You know how in high school yearbooks, they ask you a question, like what your prized possessions are? I said mine was my hair. So it was devastating—I felt like nothing looked normal. My feelings of sadness, loneliness, and isolation felt almost as if they were permeating my sense of being. I gained weight from medications and decreased activity. I had a limited collection of clothing. It felt pretty traumatic for that age.

Most of my girlfriends were supportive, even if they were ignorant—much like myself at the time. But they were busy students, and they couldn't really help me physically; I really became pretty physically dependent at this time. And many of my male friends simply fell by the wayside. Some of the men I had dated completely lost interest. I felt very lonely—and given my level of dependency, I had to move in with my parents on the opposite coast and a new place. I basically lost a huge portion of my support network.

My very first step to getting where I am now is when I received a brochure from the National Psoriasis Foundation, from my dermatologist. I really think that education is critically important. That education was the first piece of gradually learning that I wasn't alone. I was maybe 20 when I went to my first support group—I drove to L.A., probably an hour and a half drive each way, because I wanted to meet other people who had this. Somebody who knew what I was suffering from.

On the Power of Education

People are sometimes afraid of various disorders—and if it's a skin disorder there's often a fear of contagion. We're afraid of "getting" things. People in our culture are afraid of our mortality, and a disease or disorder kind of brings you face-to-face with limitations and mortality. There's also a curiosity—people don't know what to say when someone is different. People are often embarrassed to be seen looking, or to be looked at. People with amputated limbs, people with crooked teeth, people who are obese, who have facial deformities, spinal deformities, acne—all of these things, they share similar kinds of interest, curiosity, and fear from the public. Many people aren't going to be familiar with a specific condition, so it helps to come up with a pat answer so you feel comfortable, and you educate people. For psoriasis, I tell people my skin reproduces itself faster than yours does—yours takes a month to resurface and mine resurfaces every couple of days. Someone who begins to feel more comfortable in their own skin can remove that basic pat answer, maybe using humor if that feels comfortable. Humor relaxes people. As you begin to feel more comfortable with yourself and others, they will begin to feel more comfortable with you. If humor works for you, then you can share how stigmatizing or embarrassing your condition can be.

I was denied salon services once, when I went in for a haircut many years ago. Since that episode, I've frequently brought up the topic when I've gone in for a haircut, even before they begin. I used to take in National Psoriasis Foundation brochures for the stylists, because I didn't want to go through that experience again—it was humiliating. If you're proactive, you're taking the reins—you're taking charge to the degree that you're capable of. Now, when I bring it up, most stylists are like, "Yeah, we've had training." If you educate others, they can become allies.

On Literally Being Comfortable in Your Own Skin

A gift that psoriasis has given me is that I'm less concerned of what others think of me—both when I'm flaring and when I'm in remission. Of course I like looking good and I don't dress sloppily, but I'm not as concerned with my appearance as I used to be. Before I had the experience of psoriasis, I looked in the mirror more than I do now. I don't avoid them; I just don't seek them out. I don't typically wear constricting clothes; I wear a lot of natural fibers. I think it's also humbled me significantly, and has given me the compassion that I have for my patients. It's really helped me become more compassionate, because I have genuine empathy and actually understand how it feels to be 1) disabled, 2) have to deal with unpleasant treatment regimens, and 3) be concerned with my appearance.

It's also given me a sense of humor, both to help me cope and to help others feel more comfortable in my presence when I do break out. For instance, when I returned from my last absence from work, I joked about my "free chemical peel,” because my skin was constantly shedding—most people think I’m significantly younger than I am. In fact, many people who have psoriasis actually have beautiful complexions when they're not flaring, because they have constantly fresh skin. I try to focus on things like that, and work really hard at changing my perception of things. I reframe how I think about certain situations.

You have to learn to nurture yourself, first and foremost. There's a tendency to be self-critical and judgmental, and most of us place these burdens on ourselves as though they're obligations, instead of making a choice about it. Saying, "I want to do this, I know I'll feel better—my condition X will feel better and I'll be more comfortable" is going to bring you to a better, more comfortable, and healthier place physically, and probably a better, safer place emotionally. Once you do that, you can get into educating and volunteering—helping others helped me tremendously. When you're focusing on others it takes away the focus from yourself.

Another way to shift attention from yourself is to do relaxation exercises—one of the ways that those work is that you're shifting your focus, distracting yourself. Distraction is a great tool for self-care. One of the things that I talk to my patients about, whether they have health issues or not, is thought-stopping. I'll tell people to just say the word stop in their head, and that if they're in a place where they can say it out loud, to do that and clap their hands to place more emphasis on it. I tell them to think in as much detail as possible about a stop sign. Most people think about a stop sign as just a stop sign. But if you really think about it, it's octagonal, it has block capitals, white letters on a red background, the newer ones are kind of iridescent and the older ones have a flatter paint. The newer ones sometimes have a trim around the edge; there's a bolt or screw at the top and the bottom that's mounting them onto the metal post, and some of those metal posts are solid and some have little holes all the way down. There's a lot of detail there. And what does thinking about that do? It shifts your attention. It distracts you from focusing on your pain or discomfort—and that pain or discomfort can be physical or emotional.

You have to let yourself be sort of emotionally comfortable too. A lot of people with psoriasis have to pick and choose clothes that are going to be physically comfortable but allow them to feel less self-conscious. Many who have psoriasis chronically will hide it—they'll wear long sleeves, pants, long skirts, even when it's warm out or when it's irritating. They'll wear lighter-colored clothes. I'm wearing darker-colored things now that I've avoided for years and years. I love it! I actually went out and bought several black and navy sweaters because I hadn't been able to wear them in years. One of the things that I feel lucky about is that I've worked through some self-consciousness. I don't draw attention to myself, but I won't make myself uncomfortable for how I look.

You have to practice to become comfortable in your own skin. Just like when you're learning to walk as a toddler, or when you're learning to ride a bike, you fall down a lot. You've got to practice, practice, practice—and it's the same thing with being comfortable with yourself. It's not something that came easy to me at first. I can speak quite simply and easily about it now because I'm practiced at it, but it wasn't always easy. You have to recognize that it takes time, and you need to give yourself permission to make mistakes. Often, people believe they have to be perfect, even in building this skill, and that's not the case.

Body Policing Redux

My first-ever guest post! I'm so excited--particularly because it's over at Beauty Redefined, which was one of the first (and best) sites I found dedicated to examining the value we assign to beauty.

The brains behind Beauty Redefined, Lindsay and Lexie Kite are twin sisters working on their PhDs in communication at the University of Utah, studying representations of female bodies in popular media. What I loved about their site from day 1 was how it gave me specific numbers and terminology for things I'd always sensed or noticed about magazines but didn't ever examine from a data-based perspective. Whether they're breaking down why it's not men who are to blame for women's body-image issues (the patriarchy, after all, is separate from "men"), examining our willingness to accept normalized pornography, or giving us images that make us question our obsession with the numbers of weight and clothing sizes, the Kite sisters are doing excellent work worth following.

(If you've already read last week's essay about body policing, know that it's the same post--but with a better headline and far cuter graphics, even if we'll all miss the stripper-cop from the original post. Enjoy!)

Beautiful People Are Happier, Finds a Sort of Weird Study

I’m not saying the study is flawed from a scientific point of view; in fact, the study tried to control for these factors. But to call this an aggregate study that actually reports on objective measures of beauty is deeply flawed. (My own recent experience of inadvertently having AOL users essentially rate my face showed just that—same face, same picture, called everything from gorgeous to ugly.) Even if interviewers were instructed on not skewing results based on their own personal taste preferences, when asked to put a person on a five-point scale (“Strikingly handsome or beautiful” to “Quite plain” and then “Homely”), how could anyone not use their discretion?

2) Even if there were such a thing as objective beauty, and there were a uniquely qualified person who could rate each and every one of us, most of us don’t perceive beauty as a static quality. It’s interesting to note that only one of the studies used photographs as the rating tool. Others were all in person; in three of the studies, interviewers were rating subjects they presumably had only met in this clinical setting. (And then there’s the bizarro teachers-rating-kids angle—this before teachers were investigated for publicly mocking their students’ hairstyles.) One of the interviewer/subject studies had raters assign a number to the subject both before and after the interview, an astute acknowledgment of the ways in which we naturally adjust our perception of beauty according to how much we like the person.

So given this, the researchers’ note about the shortfalls of their sample studies is puzzling: ”The best possible measure would average the ratings by large numbers of individuals who have no physical contact with a set of subjects who are dressed the same way and have the same standard facial expression.”

I see their point here, sure, and my own perverse curiosity makes me yearn to see that hypothetical data. But to call this the “best possible measure” is troubling. Setting aside the question of why we’re all so eager to quantify beauty, having such a depersonalized measure would ensure that we’re essentially looking at genes, not at people—that we’re measuring beauty by who has the largest eyes, or the daintiest nose, or the fullest (but not too full!) lips, instead of whose intense magnetism makes those around them feel as though they’re gazing upon a beautiful person. I’m not talking inner beauty here—I’m talking pheromones, and presence, and gaze, and the kind of personality that reveals itself when not even a word is spoken. I’m talking the sort of beauty that is sensed through a shot to the limbic system, not the filter of one’s eyes: That kind of beauty is always going to draw attention. To focus only on genes—and what else are we observing, under the proposed “best possible measure”?—comes uncomfortably close to eugenics, and lest you think I’m being dramatic, take a look at the eerie 1852 Classification of Noses, which links physical characteristics with personality traits, and which happens to have been a favorite of major players of the Third Reich.

3) More subjects were grouped as being above-average in attractiveness than as below-average. (Canadians in particular were less willing to call out subjects as being less than average in looks. They really are more polite than Americans, aren’t they?) Obviously it’s statistically impossible for more than half of the subjects to be above-average in attractiveness, which just points to how unquantifiable beauty is. The numbers here tell their own lie. What we mean by “average” is not the average of the ugliest and the most beautiful; it’s an absence of the remarkable. And yet we can't get enough of the idea that beauty exists on a 1-10 scale, à la Hot or Not or just the mythical strut down fraternity row.

4) Women were more likely than men to reap more happiness from their good looks alone, as opposed to reaping happiness from the second-hand benefits that looks bring according to this study and others (higher income, better job prospects, happier marriages). This is unsurprising, given the premium placed on women’s looks—and it’s also being reported, so yay for that. But what’s not being reported is that there wasn’t a consistent gender difference in happiness levels. Isn’t the story here, then, that women receive less satisfaction from supposedly gender-neutral happiness factors—money, job, relationship—than men?

Thoughts on a Word: Bombshell

We first used "bombshell" to describe not a thing but a woman in the 1930s. Its use increased in the midst of early WWII jitters; American Thesaurus of Slang first recorded it in 1942. We wanted to maintain America's status as the premier manufacturer of the bombshell so much that we merged our two bombshells, painting the word Gilda (after Rita Hayworth's 1946 bombshell role) on the first nuclear bomb to be tested after WWII. Then, of course, came Marilyn Monroe, who holds the title of America's Preeminent Bombshell in perpetuity.

A bombshell encases the true threat: the bomb itself. When we label a woman a bombshell, it's unclear if we're trying to say that she might explode any minute, or if that she's merely a package for what could turn out to be a dud. Are we imbuing her with ersatz power by making her an explosive vagina dentata, or are we implying that once you take the smallest of hammers to its fragile shell, the bombshell will fall apart? "In the end, the bombshell is the one who remained the fool," writes Stephanie Smith in Household Words: Bloomers, Sucker, Bombshell, Scab, Nigger, Cyber. "The bombshell may be as volatile as 'the bouquet of a fireworks display'…but she's also just a joke. We all know that a bombshell is just a 'fat cheesy slut' [as Monica Lewinsky was described, along with bombshell] because that's just plain old common sense." And the bombshell herself may be fully aware of this perceived emptiness. Of a nightmare she had while studying with Lee Strasberg, Marilyn Monroe wrote, "Strasberg to cut me open…to bring myself back to life…and there is absolutely nothing there…the patient existing of complete emptiness." The bleached hair, the painted-on beauty mark, the rhinoplasty, the unnatural posture and voice: We all take bombshell and artifice to go hand-in-hand, but when we patent something as a prototype, as we did with Marilyn-as-bombshell, we ensure that we cannot see it as anything more complex, or more potent. When I engaged in my bombshell experiment, I wanted to believe that the bombshell was an object manufactured from an alloy of lipstick, false eyelashes, and a cascade of curls—and that beneath that shell lay something bubbling and explosive. Something nuclear. Had I thought more seriously about the term bombshell before deciding to use that as a public hook for my little experiment, I may not have used the term at all: Not only did it turn out to set readers up for an image of perfection instead of an image consisting of distinct signals, I now understand that the term is definitively no longer seen as a shell for anything explosive, but as a shell for absolutely nothing.

That is, if we even know what the term is supposed to mean anymore. Generation X- and Y-ers never seriously feared bombs. Our anxieties are more disparate: We may fear shell-less bombs, sure—dirty bombs, airplane bombs; that is, bombs without any one distinct form—but we also fear climate change, and unemployment, and overpopulation, and running out of Social Security, and Facebook, and BPAs, and fertility, and why are the bees dying? We have no one collective vessel any longer. We fear—and now, tragically, we witness—nuclear meltdowns, not nuclear bombs.

The bombshell, then, is a relic. More than ever, she is a caricature, usually hearkening back to old Hollywood—but without one collective fear-vessel, even our definition of the woman-as-bombshell morphs. She may, according to Google Images, now be rockabilly, or tattooed, or a Victoria's Secret model. She may be a bodybuilder, or a pornographic actress, or literally a cartoon. She can be anything, really, as long as it's clear that she's trying. We have lost the bomb, so we've lost the unilateral bombshell. Do we wish to resurrect her?

Beauty Blogsophere 4.1.11

What's going on in beauty this week, from head to toe.

From Head...

No, I am not done talking about Elizabeth Taylor: Rundown of Ms. Taylor's influence on beauty trends. I can't pull off the eyebrows (is it mink oil? shellac?), but the look is amazing.

...and the most ridiculous product name of the week goes to...: Nars Super Orgasm Blush. Am I a prude, or is this just too much? That color is private, thank you.

Word choice: Allure asks readers to weigh in on whether it's "appropriate" to go to work without makeup. Now, I get asking if readers feel comfortable showing up bare-faced (here's my workday-with-no-makeup writeup)...but appropriate? I just cringe a little at that word choice because it basically agrees with the Ninth Circuit Court when it ruled that certain employers can indeed force a woman to wear makeup to work. Not work appropriate: sniffing the White-Out, stealing someone's string cheese out of the pantry fridge (sorry, this wound is fresh), forcing interns to do body shots. Work appropriate: looking clean, well-groomed, and bare-faced if that's how you roll.

No-airbrush ad campaign dissected: I'll take a no-airbrush ad over an airbrushed one, I suppose—but I've been suspicious of the Make Up For Ever ad campaign since it launched. It is breaking exactly zero barriers: Their point is that you can look Photoshopped by wearing their product, not that Photoshopping to create the perfect look digitally warps our perception of beauty. The folks at Partial Objects get into this more deeply.

...to Toe

Beware the permi-cure: Long-lasting lacquer pedicures apparently can mask symptoms of health conditions. Short of something seriously funky (fungus? fur?) I wouldn't know what my nails were telling me, but a podiatrist said it so it must be true! (Though am I alone in not thinking that two weeks can't really be called "semi-permanent"? That's my normal pedicure polish duration, though manicure requires weekly.)

Most squeamish health news of the week: Toenail clippings indicate lung cancer risk. I'm picturing an ersatz oncology lab at my corner nail salon.

...and Everything in Between

Hey, Mamí: Mexico isn't known for being terribly progressive on women's rights, and street harassment both in Mexico and in the United States is a major issue for Latinas (well, and everyone else, but the machismo ethos ensures that it takes on a particular tone for Hispanic women—here's a video on street harassment and women of color). The Mexican interior ministry has developed a handbook on preventing sexist language (example: Don't say "You are prettier when you keep quiet"). Of course, a lack of street power doesn't mean Mexican women don't have purchasing power—I'm not sure what to make of L'Oréal's telenovela campaign targeting Latinas.

But let's not leave out men: Interesting that according to Latino men's self-reported take on grooming, vanidad is more important than machismo, spending more money than non-Latino men on hair styling products, moisturizer, and fragrance.

Hog balm!: It's old-timey beauty's week, apparently, between the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's podcast on 18th-century beauty tricks (the historian makes recipes from centuries ago, and reputedly her hog's lard balm is the shiznit) and a Scottish university's day of re-creating 15th-century Italian cosmetics. Finally, a way to make my body hair grow faster: bear fat!

Sustainable beauty: As nontoxic beauty products grow in visibility, more aspects of "green" beauty come to the fore. Sustainability is the new thing: The Union for Ethical BioTrade's upcoming conference will focus on cosmetics; palm oil—used in about 70% of cosmetics—isn't yet available in a sustainable form, and Thailand is hoping to get in on the action with its wealth of natural, sustainable ingredients.

The real problem with "baby Botox": Great takedown at Beauty Schooled of why we might not want to gawk and point at the "baby Botox" stage mom who reputedly gives her 8-year-old daughter Botox injections. Doing that makes it about that krazy mom and lets us off the hook for our ever-growing roster of extreme beauty standards. Remember: It wasn't long ago that pubic hair waxing was considered kinky, not mainstream. (Still, let's hope it's an April Fool's hoax.)

What up, Dove?: Love it or leave it, you can't ignore the Dove Real Beauty Campaign if you're a body-positive beauty-lover. But between last week's ad featuring white skin as "after" and black skin as "before" and their new deodorant designed to make your underarms prettier, their commitment is questionable at best.

Devil's deal?: A British survey reports that 16% of respondents would trade a year of their life for the perfect body. And while this is disturbing, it also seems alarmist. You know what? I might trade a year of my life for the perfect body too, and no, I don't hate my body. I plan on dying OLD, people, and if this fairy godmother would take away a year in a nursing home in exchange for a "perfect" body that function perfectly and looked it too (and that would forever set my mind at rest) for the next 50+ years leading up to that, hell, sign me up. The problem here (besides lack of fairy godmother) is that this isn't hypothetical. So many women have already given years of their life in pursuit of the perfect body.

Globe-trotting beauties: A guide to what international products are worth toting home. (I am at the very end of my Czech hand cream after spending last spring there. Quelle horreur!)

Uncle Sam wants you: Maybe not Uncle Sam, but his little brother, or maybe a nephew—let's call him Frederick? FDA Frederick wants you to fill him in on bad reactions you've had to cosmetics. As a reminder, there is virtually no regulatory oversight on cosmetics, which explains why there is lead in things that you put on your lips and why it's totally legal. This is your chance to contribute.

To Shampoo or Not Shampoo?

This time around, the question isn't: Should I cut my hair? It's: Should I wash it?

I've been evangelical about the no-shampoo thing (for those new to my experiment: I haven't shampooed since September, just rinsing and conditioning my hair once a week and using a hair powder in between), and while I've tried to be honest about the drawbacks, part of evangelism is sort of glossing over the downside. So, to be clear:

PROS OF THE UNWASHED

1) My hair is incredibly healthy. No split ends, thick, strong, resilient.

2) I have more time in the mornings.

3) I have more volume, and a fetching bedhead look. (Amiright amiright?)

4) My hair holds styling easier (I am still a big fan of the updos)

5) The longer I go, the more normal it looks.

6) Cred.

CONS OF THE UNWASHED

1) Let's be real: It can get greasy.

2) As shampoo-free Alexandra Spunt writes in No More Dirty Looks: "It's not that it stank.... But it smelled like hair, and I wanted it to smell like girl hair."

3) When I'm self-conscious, it goes onto the list of Things People Might Be Looking At, right below my extraordinarily sharp incisors but before my worry lines.

4) Getting my hair wet now seems like an enormous ordeal. I'm now understanding where the "I'm washing my hair" turn-down line came from.

5) I just don't feel clean.

As Christa d'Souza wrote in W, "I can’t help feeling like a piece of vintage clothing that hasn’t been properly dry-cleaned." It's not that I feel dirty; it's that since September, I haven't felt that super-clean, super-breezy feeling you get when every inch of you has been properly scrubbed and rubbed and cleansed and patted dry. And I miss that feeling, particularly after a great session at the gym where my body feels all stretched and fantastic...and that feelings ends at my scalp.

But, dammit! At this point I've reached the pinnacle of We Great Unwashed: My natural hair oils have coated the entire length of my strands, my hair is in great shape, and it's almost summer (humor me here), which means updos, which will take care of problems 1-4 above (I don't bother to blow-dry my hair when it's going immediately into an updo, so getting it wet isn't a problem). I'm not sure whether to consider my time investment a sunk cost or to charge forward.

Hmm. I ask the Washed and the Unwashed alike: What to do? Giddily shampoo? Try baking soda and apple cider vinegar? Be a hair warrior and stay unwashed? Another option altogether? Be candid now, please. And vote in the poll on the sidebar!

PS: Still haven't washed my face. That, for whatever reason, feels totally fine.

Body Police: How I Unwittingly Escaped the Body Cops

This kerfuffle at This Recording piece about body policing stood out to me, not because it said much new, but because of the response to it. It's one of the "skinny people aren't exempt from nasty comments about their bodies" pieces out there—a point well taken. What doesn't go over well is when the author of the piece claims that "Few nice, everyday folks would approach an overweight stranger and tell them to go on a diet." While most quit-talking-about-our-bodies attention yesterday was directed toward The Sartorialist (where 1,106 people commented on his preference for only mentioning his subjects' body size when they're not bone-thin), there was enough harrumphing from the always-awesome Kate Harding for me to take note.

So we're agreed that we shouldn't be surveilling and policing other people's bodies, right? But that because our culture attaches so much to women's bodies, there's little way to escape it, right?

Yet for years, I did escape it. For a chunk of my twenties, I inhabited a size zone that, on my medium frame, made me look a little more than medium. I was a few pounds overweight by the BMI scale (and yes, I know BMI is faulty, but I have the kind of body that it was designed for--when I'm moderately active and eating my nutritionist-approved meal plan, I'm squarely in the middle of the "healthy" zone) but didn't have trouble finding clothes at mainstream stores that fit me. Basically, I had about the body of the average American woman. And nobody said a word about my body. Ever. Nobody called me curvy, or average, or normal. Or voluptuous, or fat, or stocky, or plump, or soft, or sturdy, or thick, or anything. I wasn't hiding my body: I didn't flaunt my figure, but neither was I dressing in paper bags. When shopping for clothes, I went into a store, found things I liked, tried them on, and bought them or didn't. In "body talk" with friends, nobody commented on my figure. It was a non-issue, I thought.

Around age 30, I lost a lot of weight for a variety of reasons—I stay away from numbers and sizes here, but as a frame of reference, I lost nearly 20% of my body weight. I didn't look emaciated or anything near it—the #1 word people used to describe my body at that time was "healthy." (The writer whose piece prompted this entry was frequently suspected of having an eating disorder; only one person ever inquired about my mental health in that regard.) Healthy, then trim, and slender, and lean. And cute, and little, and, yes, skinny.

That is: In dropping three dress sizes, I also lost my protection against body policing—a protection I didn't realize I'd had.

Sure, some of this came from friends and coworkers, who had a point of comparison and were commenting on my body as "little" compared to what it had been. (And note that I was well within the "healthy" BMI range even at my lowest weight, and looked it.) I didn't mind that—they were trying to be supportive in what our culture frames as some great, noble battle against fat. In fact, with a handful of exceptions, most people were refreshingly sensitive about how to frame their compliments so as not to put me on the spot or imply that I hadn't looked fine before.

What surprised me was the reaction from strangers. Shopkeepers suddenly started guessing my dress size, almost making a game out of it at times. Some criticized my body in ways they hadn't before; my figure was "fantastic...but you've really got to have a flat belly for this dress." People I'd just met made quick assessments of and references to my body in cocktail conversation: "Oh, you wouldn't understand, you're thin," or commenting on my food. People I was meeting for the first time made assumptions about my character: I was "disciplined," or had "willpower," or exercised "control." Most often, I was simply "good." I was "lucky." I rarely got the kind of "I hate you" thing you hear about sometimes—I wonder if it's my friendliness or the fact that I wasn't super-slim that protected me from that particular form of policing—but on occasion, it did float my way.

At my heavier weight, it was understood that even if I wasn't fat, I was at a size where people assumed I probably wanted to lose weight. And because weight is a sensitive issue, this unspoken weight-loss dictum was off-limits for discussion. I'm certain that it would have been different had I been unabashedly fat, as many a tale from fat women illustrates. (Dances With Fat always dissects these in a delightfully tart manner.) But because my body was nearly the exact proportions of the average American woman, it was like I was in a sort of DMZ of body policing: Too small for CDC-approved admonishments about my food intake, too big to make a game out of guessing my dress size, I skated through most of my twenties unaware of how freely people comment on one another's bodies.

Now, there may have been other reasons for the spike in body policing I experienced when I lost weight. Maybe it's because people picked up on the hungry discomfort I felt at my lowest weight and were either trying to reassure me that it was "worth it" or exacerbate it for their own weird-food-issues reasons. Maybe I carried myself differently. Maybe my fleshier body lent me an air of "fuck your fascist body standards" confidence that people didn't want to mess with. Maybe I blocked out negative (or positive) comments I got when heavier. Maybe I clinged to the body policing I received at my lightest, for even when there was an undercutting tone to them, the fact was, I had wanted to lose weight, and such comments were validating. Maybe even now that I've settled into a weight that's between my highest and lowest and that feels natural to me—and now that most of the body policing comments have dwindled—I'm still filtering the comments I received in order to remove whatever body-image issues I have and make them about "culture" and "society" instead of my relationship with my body.

I hesitate to draw grand conclusions from this. First of all, I'm guessing that there are plenty of average-American-woman-bodied women who've heard all too much from others about their figures. Second, I've argued here plenty that if you're a woman, your appearance becomes a comments free-for-all. (And I'm certain that I wasn't actually exempt from body policing at my heavier weight; I was just free from the vocalization of it.) But what I'm gleaning from my experience is that while women's faces and figures are forever targets, we attach highly specific meaning to specific shapes and sizes, and we make assumptions about people's personalities and histories based on this one piece of evidence alone. It's not a spectrum of positive assumptions assigned to thin people and negative assumptions assigned to fat people, nor is there a neat flipside-rhetoric working in which we champion fat people while demonizing the thin. Our attitudes toward the bodies of others are only as complex as our attitudes toward our own.

Thoughts Upon Reading 122 Comments About My Face, Courtesy America Online

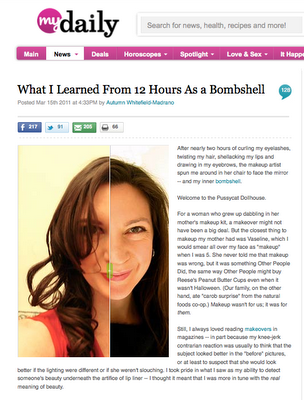

"Your story is being considered to be featured on AOL Welcome Screen!" my editor at MyDaily wrote me in regards to the piece I wrote about my makeover. "If it happens, you will get TONS of traffic. Yay! But be ready for crazy comments."

I wouldn't say that the comments were crazy (with the exception of "I would eat her with a spoon"). But when I was notified that it had gone into rotation and saw more than 100 comments within mere hours, I was both thankful to my editor for her prescience (word up, Ellen!) and interested in what this sample of people might illuminate about our culture's attitudes toward beauty. I sometimes fall into the pop-feminist bubble (I remember being shocked when a friend told me he hadn't read much discussion of Natalie Portman's ballerina-fied body in Black Swan, whereas that was pretty much the only thing I read about the film), so I was curious to see what a cross-section of Americans who are Online might have to say about my piece. And, of course, I never found out: They were too busy talking about my face instead.

What I learned from 122 comments about my face:

1) People overwhelmingly preferred the "before" me: “I agree with everyone else the before picture is better than the bombshell photo. ; )”

I prefer the "natural" me too, for that matter—I loved the bombshell look and found it fun, and thought Eden did a fantastic job of creating the look. But I wasn’t doing the makeover to look better; I was doing it to look different, and both my makeover guru and I approached it with that mind-set. And, sure, it's nice to hear that Online Americans don’t think I need a pile of false eyelashes to look nice. (You like me! You really like me!) I admit it's also a relief. (Still, I stand by certain tricks I learned. Eyebrow pencil! Lipstick!)

Aside from that—and aside from the unfortunate difference in lighting between the two photos, which ensured that my “before” has a naturally-lit quality that the “after” couldn’t achieve—I found it interesting that, in fact, only four commenters flat-out said that I looked better afterward. Is it only a straw man who prefers artifice? And was there an element of self-congratulation among some commenters? It’s easy to be drawn to certain signals of beauty: red lipstick, emphasized eyes, long curls. Therefore, it’s easier to reject those signals as false, vain, trying too hard. Yet we all know what those signals mean, so I wonder if some commenters thought that they were seeing beyond the surface by preferring the more low-key look presented in the “before” picture. To reject my utterly normal-looking, friendly-seeming “before” picture would be more akin to rejecting a person, not the symbols presented in the “after”—and while anonymous online commenters aren’t known for their social graces, neither are people usually out to merely be mean. (Of course, plenty of commenters were just that, but they’re easy enough to discount.)

2) The catch-all insult: “got 2 mention nose job.”

A handful of commenters indicated that I needed a nose job. Whaaaa? I have the most average nose in North America. I mean, am I deluding myself here in that there is absolutely nothing remarkable about my nose? (Okay, I do have a bump from a reconstruction after a car wreck when I was 16, but you can only see it from the side.) What this indicates to me is that “you need a nose job” is a grab bag of ways to put a woman in her place. It makes me think of the time a random man on the subway suddenly started yelling at me about how fat I was. It wasn’t that I was fat (I’ve got a medium build), nor was it even that he thought I was fat, I’m guessing—it was that he was putting me in my place for not encouraging his advances. You can’t see my body in the shot that was on the page, and telling a woman she needs a nose job is vaguely the facial equivalent of “fat”: It’s a catch-all way of saying, There is something wrong with you, even if there isn’t. (And not that being fat or having a nose that is the stuff of magnificence is “wrong,” but some people treat it that way.) I’m not everyone’s cup of tea, but neither is there an odd-looking feature about me that’s so outstanding as to become the butt of commenters' jokes. So: nose job it is.

3) Total strangers could tell I'm uncomfortable in front of a camera: “She would be prettier in each picture if she had actually smiled rather than pursed her lips.”

It’s humbling to be called out on your “photo face” by total strangers. (A number of people commented that I looked pinched, uncomfortable, or “like she’s sucking a lemon.”) After interviewing photographer Sophie Elgort, I had to own up to the fact that if I’m trying to “look pretty” in a photograph, it will kill any chance I have of looking pretty. As Sophie said, “How can you expect to look like your best self in a photo if you’re putting on a ridiculous face?” To see that total strangers could pick up on my discomfort was an official notice that I’m not fooling anyone when I pout-smile in front of the camera. Smile and breathe. Smile and breathe.

4) People were quick to point out that, no, I didn't look like a bombshell: “We have very different definitions of 'bombshell'”

Some commenters meant this is a put-down (“More dud than bombshell,” courtesy icebull), but others just seemed mildly perplexed. I realize that a look that’s over-the-top to me is tame by many standards ("I'd like for you to visit Tuscaloosa on a nice fall Saturday—chances are there's more bombshells walking around there than where you're from,” writes DC). Perhaps the word conjures something that I didn’t intend; I forget that not everybody scrutinizes words the way I do. But from my perspective, the whole point of the bombshell is that it’s a creation, not a God-given quality. (Norma Jeane, anyone?) So when commenters wrote along the lines of, "She's just wearing lipstick and eyeliner! Where's the bombshell?" I wondered what they were hoping to see. Did they expect something more over-the-top? A different look entirely? A professional-level photo? Someone who is flat-out more beautiful than I could ever be?

Or was it that the term is so loaded that it can’t help but disappoint? We’re saturated with images of professional beauties everywhere, and those images are always digitally manipulated. I wonder if some users who saw the “bombshell” promise on their welcome screens, upon scrolling over my “before” picture and then finding a non-airbrushed, non-professional picture of a non-model—that is, an average woman who has been promoted as a “bombshell”—simply felt ripped off.

Listen, I don’t think I’m some exquisite orchid, but I can look in the mirror and see that I’m not “horrifying,” as one commenter wrote. I’m guessing that the people who were eager to put me down were doing so because through the construction of the headline, the “grand reveal” drag-and-scroll rollover of my before and after, and the very idea of the piece, I was claiming “bombshell” status for myself, however temporarily. It was that claim that provoked a response, not how I actually looked. In the days following Elizabeth Taylor’s death, I had a handful of conversations with friends who said something along the lines of “She’s pretty, sure, but why was she known as a great beauty?” None of the people who said this to me are the type to just randomly detract from someone’s looks: They were saying it in response to the sudden hyperconsciousness of a woman who has readily been called the most beautiful woman in the world. Of course they were going to look at that claim critically—and when you're using that rubric, Elizabeth freakin’ Taylor can fall short. Once I asked readers to take me in as a bombshell, how could I stand a chance of escaping the same?

5) Few people read a single word I wrote: “She was so excellent at playing Cleopatra that the world later really thought that Cleopatra was actually white. God Bless and Rest in Peace.”

Which is to say: Few appeared to have read the piece itself. The grand total of people who referenced anything other than my photo? Thirteen. (That’s excluding friends and readers of The Beheld who commented to help promote the piece—thank you!) Of those, maybe five actually addressed the points I was attempting to make. I can’t really get up in arms about this: It is a piece about my appearance, after all; referencing my looks in the comments isn't irrelevant. But nowhere did I say in the piece that I thought I looked better in either photo, and for a piece about getting a makeover, it was as far away from “which is better?” as you could get.

But none of that matters, because nobody was reading. I'm recalling an anecdote I didn't have room for in my interview with artist and writer Lisa Ferber: She was nervous while preparing to share one of her short stories at a reading. "My mother asked me if I was nervous about the piece, and I said, 'No, I'm nervous that I just won't be a good reader.' And she said, 'Lisa, you are a beautiful woman—nobody is going to listen to a word you say anyway.'" We both laughed when she shared the story, but it stuck with me. I’ve seen plenty of women be underestimated because they’re pretty, but I’ve always assumed that because I’m neither glorious nor hideous, it didn’t apply to me.

What I learned with this piece was that being objectified isn’t about whether a woman is pretty. It’s about her being an object—which is mighty hard to escape if you’re a woman, regardless of your appearance. In this case, the subject matter served as an ersatz carte blanche for people to openly discuss my looks, but it’s not hard to think of examples where the subject matter was entirely incongruent with a woman’s looks and people took aim anyway. (The 2008 elections come to mind.) I can’t imagine that people would have read the piece any more closely if I’d been outrageously weird-looking, or that fewer people would have read it if I were more conventionally beautiful. It was that I was a woman, and that I was there.

Beauty Blogsophere 3.25.11

But maybe I'm just jealous of people who know how to use eyeshadow?

Singles: I usually snooze my way through beauty product slide shows (look, it's shampoo! look, it's more shampoo!) but thought that this one was actually useful—a roundup of single-use beauty products. (If I were at all entrepreneurially minded I'd be using these for my product kit, The Shack Pack, which allows ladies who may or may not be sleeping in their own beds every night to have a wallet-sized kit with all things cosmetics. Business majors, take it away.)

Cosmetics cheerleader: Jane Feltes at The Hairpin gives fun beauty advice every week, but what's particularly noteworthy here is her shout-out to women like me, who are self-conscious about makeup but still want to play. "Everything stands out when we’ve never done it before, but trust me, no one else sees it that way. They all think you're 'so put together' today."

Say cheese: Non-promotional pics of the Photoshop camera, from Allure. The more I stare at the "after" photo the weirder it seems. I get that it's nice to not have to put on powder every time you snap a photo (I'm a shiny gal myself) but other than that I truly think that the alterations aren't doing anybody any favors. Her forehead looks strange in the second one, probably because IT'S NOT HER REAL FOREHEAD.

Beauty quotient: Nice piece on HuffPo about inner beauty, and the combination of qualities that make a woman beautiful, and how we're all individuals, and blah blah blah. It would be a helluva lot nicer if it weren't written by a man who's made his living as a plastic surgeon specializing in faces and boobs.

...and Everything in Between

Growing up ugly: Amazing post about what life was like as the resident "ugly girl" in high school. I remember "that girl" in our high school—the one everyone teased, the butt of every joke—and always wondered how it informed her adult life. The common wisdom is either that it seriously messes someone up, or that they go on to be a rock star supermodel and they've shown us! This engaging, thoughtful essay shows what one woman gleaned from having to rely on a different barometer than most of us do.

But just in case that isn't enough: A guide to "surviving the uglies" at Eat the Damn Cake. I usually want to hide in my yoga pants when I'm having an acute case of these, but know I always feel better when I wear something a bit more structured, and to see it and other ideas laid out here was nice. (Though why do people always recommend taking a bubble bath? Where do these people live where a bathtub is comfortable?)

The privilege of pretty: Lovely meditation at Seamstress Stories about how recognizing the privilege of beauty enables one to more easily reject it.

Dove's dirty deeds: From the company that has done some nice work on women and self-esteem, an ad that truly seems to imply that black skin is "before" and white skin is "after." No, I don't think it's a coincidence. As a commenter at Sociological Images says, "These companies have psychologist and sociologists working on these ads that specialize in people’s – and in particular the white upper class women this ad is aimed at – reactions to advertisement. If it were an accident, they would catch it. Period."

Giving to Japan: My philosophy is that if you care about a cause, you should donate directly to it—time, money, effort—instead of merely engaging in consumer activism. You'll feel better about it, and it's a greater act of generosity, both in direct impact and in feel-good energy. And though some companies have a truly excellent record of philanthropy, it's also an easy out for organizations that don't really give a shit to go on record as having done something. (International Cosmetics & Perfume made the tremendous sacrifice of donating fifty—yes, that's five-zero!—Hanae Mori reusable tote bags, originally intended as an in-store customer appreciation gift, to the American Red Cross to assist Japanese displaced from their homes and belongings.) That said: If you're planning on stocking up on certain products, here is a nice roundup of major companies that are donating some proceeds to aid with recent events in Japan.

The yoga tax: Connecticut legislators are considering dropping the exemption of commercial yoga studios from the state's commercial tax. Health clubs are currently exempt from the tax, but nail salons and pet grooming are being considered for inclusion into the new tax scheme as well. I'm all for yoga—Cat and Cow, yo!—and think it should be treated as a health and wellness area, not beauty. But honestly, a lot of the commercial yoga studios have that...yoga...thing that sort of icks me out and makes it about "achieving" a certain lifestyle, and is it terrible of me to say that while I want as many people as possible to do yoga, I'm not exactly crying tears for certain Connecticut yogis? Can there be a one-person committee consisting of me that decides which studios are about health and wellness and which are about who has the cutest yoga mat?

Elizabeth Taylor: Amid all the press surrounding her death, a few pieces stand out as far as what's of concern to me as a beauty blogger. ABC News looks at her as a template for celebrity fragrance; Virginia at Never Say Diet examines her as a body image role model; and NYTimes style writer Cathy Horyn investigates the intersection of fashion, era, beauty, and image that Ms. Taylor embodied. Edited to add this nice quote roundup from beauty professionals, including Ted Gibson, Eva Scrivo, and Tabatha Coffey, paying tribute to her.

Elizabeth Taylor, 1932-2011

But then—then, there's Elizabeth Taylor. Elizabeth Taylor, whose beauty from youth through adulthood was remarkable in the true sense of the word: We cannot help but remark on her beauty, so present, so stunning it was. I recoil when I hear women reduced to their physical parts, and the way that some well-meaning people have tried to fix that is to separate physical beauty from other assets. And it is a separate beast—both in the importance we place upon it and the way in which we treat those who have it—but what we're eager to overlook in our quest to be seen as whole is how possessing great beauty can inform those other assets.

In the case of Elizabeth Taylor, her beauty informed what made her so compelling. Her beauty wasn't the sum of her gifts, but without those eyes, that complexion, that face, our eyes may not have been as open as they were to take in her gifts. We root for her girlish innocence in National Velvet; we adore her kittenish yet womanly charm in Father of the Bride; we're riveted by her boozy glamour in BUtterfield 8. As artist Lisa Ferber says in my interview with her, "Whenever we hear about the beautiful but tortured woman, we don’t really believe it, which is why we love it." It's a point I agree with. Yet every rule has its exception: Elizabeth Taylor's talent and notorious personal life gave us the voyeuristic pleasure of both. We saw her beauty and took it as fact; we saw her torture and believed that it wasn't contrived for our attentions. In her case, we do believe it. Even in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?—a role that people sometimes point to as where the veneer starts to visibly crack, where we see her mortality—her beauty is as much a part of the character of Martha as is her cruel wit and her covert swamp of vulnerability.

What we see in Elizabeth Taylor's face is an enormously complex story of beauty itself, played out over a lifetime. She had a quality that spoke to something I couldn't articulate about being a woman: She seemed too smart to simply let herself be objectified, but appeared to take pleasure in being looked at. I think of the iconic shot of her leaning against the door in a white slip, booze in hand, exposed as being both effortless and sculpted. It wasn't merely that she was "smart AND beautiful!"—many are that. Being smart and beautiful is past the point of being remarkable. It was that part of her intelligence seemed to stem from her interpretation of her beauty. I felt, in fits and glimpses, as though she were speaking for every woman whose complexity and vulnerabilities were as exposed as her slip: She taught us that what made a vulnerability a vulnerability instead of a mere weakness was that it is surrounded by strength. At times I felt as though she were speaking for every woman of that ilk—which is to say, most of us. At the same time, her own life was incredibly—laughably—different than ours. She seemed to be in another stratosphere. It's no surprise that she befriended Michael Jackson, another icon who reflected a deep urge within our culture while simultaneously crafting his own unintelligible freakdom.

Elizabeth Taylor had the gifts, and the opportunity writ large, to communicate the complexities of beauty to us. She took the arc of the tragic beauty and imbued it with a rich, electric vibrancy that defies the eye-rolling cynicism people might want to apply to this counter-tale. She made it impossible for us to ignore her, as a beauty, as an actress, as an icon, as a woman. I will forever be a fan.

Thoughts on a Word: Attractive

Attractive is the base level. It is a series of facts, opt-ins or opt-outs: attractive is tidy, inoffensive, general. Attractive is a matching purse and a fresh haircut. Attractive is the safe zone, a step away from beautiful or alluring or even pretty; attractive is a way of speaking about one's looks without revealing vanity or arrogance. Attractive is a quiet, inexact mimicry of some of the traditional, lasting hallmarks of beauty—symmetry, proportion—accepting them where we're graced with them, deflecting or accepting or shifting where we're not. You cannot argue with attractive.

"I wouldn't say that, but yes, I'm attractive" or something similar is the #1 answer I've received when asking interviewees if they think they're beautiful. That's not to say there's no overlap between attractive and beautiful, but rather that beauty is about something we can't necessarily control, whereas attractive is more about showing that you're playing ball than it is about any particular effect or feature. "Anybody can make themselves attractive with a little effort," says one of my interviewees. "We all know what makes someone attractive or not attractive, and it's something that all of us can attain," says another. Beauty can range from oligarchy to plutocracy to even anarchy, if we're each our own pilot nations shapeshifting into beautiful depending on our mood, the light, our neighbors, whether we're in love, combustions of time, place, and genetics. Attractive is a democracy.

It's odd, though: attraction, even more than beauty, is subjective. I can't choose who I'm attracted to any more than I can choose whether I like the taste of Vegemite. It's a pull that's undeniable, even when we're talking about a strictly platonic relationship—we've all suffered from a lack of attraction, meeting people we really, truly, genuinely like and have a lot in common with but never really click with, right? And we've all met someone we shouldn't want to be closer with but yearn for anyway, right? We can control how loud we allow attraction to speak, but the fact of it, on some level, is out of our hands.

Yet we choose a word based on this unpredictable, indefinable chemistry—or is it physics?—to serve as our safe word, our base line, our beauty democracy. We choose a word that, at its heart, is about pheromones and sex as a way of discussing a sort of neutered beauty. Or is it that with attractive we're simply saying that, at its base level, an attractive person has the ability to attract, even if it's not the speaker whom s/he is attracting? Is that where the democratic connotation of attractive comes in?

I'm not arguing that we redefine attractive: We need a safe word. We need attractive both for its gracious ability to let us talk about beauty and appearance while managing to deflect inevitable accusations of conceit, and for its potential for magnetism. I simply wish for us to consider its source, consider its democracy, and consider it not as a lesser-than form of beauty but rather a tool we can use to examine something as complex and elusive as beauty, and a tool we can use to excavate what it is we're really after.

Beauty Experiment: Update and Confession to the Scientific Community and the Community at Large

Let the official experiment log, i.e. this weblog, reflect my personal conflict over adding a factor to the experiment midway through, in what I admit is a rather haphazard fashion. I felt it better to attempt a corrective course so as to not begin the experiment anew (and since in other capacities besides that of chief scientist, I'm a laydee who doesn't want to walk around with half of her nose shedding). My hope that my integrity remains intact in the eye of the public.

Thank you, and good day.

Beauty Blogsophere 3.18.11

From Head...

Hottentot Venus hollaback: Interesting take on toxic cosmetics and why black women are particular targets of "dirty" products--nice historical look.

I got a B- in chemistry but liked this anyway: Science-oriented breakdown of the future of green cosmetics. That's clean/natural cosmetics, not St. Patrick's Day eyeshadow. (Via Safe Cosmetics.)

Eastern bloc beauty: Tidbits on the globalization of beauty: The last state-owned cosmetics company of Bulgaria is being sold (it was privatized in 2002, the last one to do so), and "aspirational shopping" hits another former Iron Curtain area, the Ukraine. I'm particularly amused by the fact that the Ukraine is such a rich source for beauty labor--models--but imports 98% of its beauty products.

...to Toe

Meanwhile, I'm still pissed that I lost on "maverick": "Pedicure" is the winning word in Fort Wayne, Indiana, fifth-grade spelling bee.

Sole mates no more: The end of the scandalous saga of "the Heidi Klum of foot models" and her doorman-turned-husband-turned-

Welcome to her dollhouse: I'm not surprised to read that Eliza Dushku is pretty frank and articulate about body image issues. If any of the other twelve people who watched Dollhouse are reading this, you know what I mean: The show presented the usual Wheedon-voyeurism-feminism conundrums but was an interesting exploration of bodily ownership and personal agency. She's not saying anything you haven't read before, but it's nice to hear anyone in Hollywood speak at length about this--usually there's just a quote sandwiched into a profile for good measure.

Fashionable feminists: Fantastic, thought-provoking answers from feminist fashion bloggers in answer to the question "How do you express feminism in the way you dress?" (Mrs. Bossa's post is excellent, and scroll down for a list of bloggers who answered this, myself included.) A lot of talk about labor--labor of the wearer and, of course, of the people who make the clothes we wear--and the gaze, objectification, aesthetics, celebration, and just love of fashion, always written with an intelligent, feminist eye.

Reverse engineering: You know, for all the talk about Photoshopping, we don't frequently hear from the people who are Photoshopped. So while the original poster at Good makes some nice points about the use of photo retouching when representing "real" people--in this case the first female engineer to grace the cover of Wired--what's truly thought-provoking here is the engineer's response. "If I'm happy with this and I say it's looks like me isn't that GOOD :)" The real problem here, it seems, is that it's two thousand frickin' eleven and Wired is just now getting around to putting a woman engineer on the cover. (Also, while I think she looks great, and I also love Rosie the Riveter, can we think of something else that represents capable women? And no, Wonder Woman doesn't count. Are there really so few icons that we must resort to Rosie again and again and again?)

Race, Eating Disorders, and Body Ideals

add to the black-woman objectification pile-on. So!

Which brings us back to the thinness of black South African models. Model Carol Makhathini reports that the dichotomy exists because black models are automatically assumed to be larger than white models, increasing the thin imperative. It makes sense on one level, but certainly black women are assumed to be larger than white women in the States, and it doesn't play out that way in thinness-obsessed America. Another possibility is that South African women are playing out history on their very bodies. Apartheid ended in 1993, but given the preponderance of racism in the U.S. nearly 150 years after the Emancipation Proclamation, it's not surprising that racial tensions and other forms of racial inequality run high in South Africa. Combine that with it being the world's leader in raping women, and suddenly black South African women's bodies can be seen not as their own, but as symbols—symbols of legacies of the past, hopes for the future, of a race-gender war that will take generations to resolve. It's unclear whether black South African models suffer from eating disorders in greater numbers than their white colleagues--but research indicates that black South African women display greater eating disorder pathology than other ethnic groups, and at comparable rates to white women. But eating disordered or not, black models' bodies hold more potential for projection in a nation where race is so distinctly loaded. It's no wonder that their bodies are more molded, more sculpted--and are literally less--than those of their white peers.

How I Express Feminism in the Way I Dress (or Not)

It's Fashionable Feminist Day in this lil corner of the blogsophere. And I don't consider myself a fashion blogger (I still can't say "I write a beauty blog" with a straight face), but there's certainly overlap. I've always enjoyed playing with makeup more than I have shopping for clothes, and in fact the latter usually feels like going to the dentist. As great as it feels to occasionally put together a bang-up outfit, the fact is most of the time my mind just doesn't work that way. I try to wear what looks good on me and what I can put on without thinking about it too much, and leave it at that.

But the minds behind Fashionable Feminist Day asked this question: How do you express your feminism in the way you dress? And my answer surprised me.

Fact is, I don't. In fact, sometimes I dress in ways that go against my feminism. I think we're all past the point where we can say that the answer to "Can feminists wear high heels?" is a loud, heel-stomping "Yes." Because, duh, it's fine for feminists to want to look hot, because we're embracing our sexuality, and if that means wearing stilettos that means wearing stilettos and YOU GO GIRL, you ROCK ON WITH YOUR BAD SELF.

And, okay, I'm fine with that--but if we end the conversation there, we're robbing ourselves. Of course there's nothing wrong with feminists wanting to look pretty! Most feminists I know are! But I can't escape the fact that when I don a pair of high heels, I am prioritizing the line of my leg over comfort, mobility, and health. (I have lower-back issues, so this is a health issue for me.) Still, I wear them, and like them, and like the way I look in them, and indeed like the way I feel in them—more put-together, more sophisticated, more polished. Just like the makeover that won't die, wearing heels expresses a part of me that often goes silent. I like hearing the click of my heels on the pavement; it makes me feel like I'm a part of what makes this city so special--more so than when I'm, say, sitting at home in my yoga pants despite having done no actual yoga today (does doing the neti pot count?). But that professional feeling--that slick, city-girl feeling--is about my abilities and work history, not my shoes, right? Or at least it should be, because isn't that the entire goddamn point of this feminist thing?

I'd be lying if I said I didn't feel conflicted about the way I sometimes present myself. The minute I prioritize my looks over my own personal comfort, I am doing something that goes to the core of what I believe--about myself, about gender roles and expectations. It's not enough for me to say that it's fine to be "feminine AND a feminist" as if that's a surprise to anyone. Sure, some still equate feminism with hairy-legged man-haters, but the company I keep has progressed beyond that point. It's not enough to just say "Oh, it's my choice so it's fine": It is my choice, yes, but wearing shoes that can't carry me comfortably for eight hours isn't a choice I'd make if wearing high heels didn't connote something about myself as a woman that I wish to project. I don't damn any woman for how she presents herself--I don't think--but I do know that as full of bravado I might feel leaving the house in a cute pair of heels, by day's end I'm wondering if it's worth it.

So, what can I do as a feminist to reconcile my self-presentation with my politics? I can ask questions. I can explore the reasons why we wear what we wear; why we present ourselves the way we do. I can listen to the smart, sharp feminists who don't feel this conflict, either because they've fully embraced the contradictions or because they've made choices that are more aligned with their politics. I can listen to non-feminists too, and learn from them: Not every woman who shuns makeup and dresses solely to please herself identifies as a feminist, and they have lessons to teach me. And every woman I know, feminist or not, has given thought to the face she presents to the world. Whether she critiques it, engages with it, challenges it, or jumps in wholesale, it's not a blind choice, and there's an intention behind it. Looking at those intentions is at the heart of what I'm trying to do here at The Beheld.

I don't expect to come to any grand conclusions or even to change my actions--I like wearing high heels, I like having that extra little oomph. But without examining it, or by blithely stating that it's my choice and I'm a feminist and so therefore it's a feminist choice, I stop short of the place I'd like to wind up.

Al-Qaeda's (Supposed) Ladymag, and How It Connects With American Women's Magazines

It’s news because a women’s magazine seems like such an unlikely place to spread a wider, uglier agenda. But pointing and gawking belittles the ways in which women’s magazines have long been an effective awareness tool for those who know how to use them. Al-Shamikha seems off mainly because the end goal is so distasteful to us, not because its means are so wild.

In the States this is most clearly illustrated by coverage of women’s health issues, which is arguably the #1 service that women’s magazines perform for their readers. Ladymags tend to be vocal about advocating reproductive rights, at a time when those rights are in peril. Women’s magazines are hardly working on behalf of lefty legislators—but certainly legislators who battle for reproductive rights have an enormous ally in women’s magazines, an ally that is schooled in personalizing issues that can get lost in a sea of rhetoric and misleading information.

It’s not just women’s health, though. The magazines most frequently thought of as the smart-girl women’s mags have earned their cred in other ways: hate crimes (here in the form of honor killing), unionizing (“A Girl’s Guide to Unions” in May 1967 Cosmo is sandwiched between “Why German Men Are Insane About American Girls” and “How to Behave on a Boat”*), sex trafficking, cults that target young women, and undocumented immigrants. There aren’t political machinations here, but there are plenty of people in the industry eager to advance women’s political agendas.

It’s overall good news that magazines treat women’s lives more comprehensively than just fashion and beauty. That said, when the information gap is being filled with information that seems exotically abhorrent—as is the case with “Jihad Cosmo”—it calls into sharp relief how weird it is that we want to lump beauty tips in the same outlet as news coverage. The juxtaposition of beauty tips with extremist advice makes us double-take because it seems downright bizarre, but it’s only bizarre because we can’t imagine any women’s magazine telling us to marry a suicide bomber. We can, however, imagine a magazine asking us to take action that fits more into our paradigm. The propaganda tool just takes the model of women’s magazines—a model we all accept—to its logical, and extreme, conclusion.

The shock! horror! mockery! knee-jerk reaction about the “Jihad Cosmo” points toward a combination of xenophobia and righteous anger toward Al Qaeda, using what is a legitimate tool as bait and turning it into something ludicrous. The Daily Mail singles out bits about the niqab without acknowledging the complex history of the veil, and points out how the magazine directs women to not go out except when necessary. But I remember reading ladymag advice about using Twitter as a safety tool—I could tweet wherever I was going so that when I was inevitably abducted, my followers would know where to start looking for my body, or something like that. It’s not the same thing—but suggesting that women basically install auto-tracking devices isn't actually that far from “Don’t leave the house.” And while it seems extreme to suggest that veiling one’s face is an effective tool against sun damage, is it any weirder than suggesting that dieters pour Diet Coke and Splenda over a cored apple to make “apple pie”? (Yes, that was a real tip.)

Other stories in Al-Shamikha have more direct counterparts in American women’s media: Al-Shamika and Allure both caution against “toweling too forcibly”; Al-Qaeda martyr widows and Operation Iraqi Freedom war widows are each given treatment, the latter in Glamour. As for staying home to avoid sun damage, Fitness tells us to stay out of the sun—after an expensive, painful chemical peel, which, depending on your perspective and pain tolerance, is nearly as drastic in its own way. (Actually, this has me thinking about some sort of cross-cultural beauty tips exchange. I’m picturing editors at Allure donning niqabs.)

All this is complicated, of course, by the strong possibility that the magazine is a fake. Which I didn’t mention earlier because I wanted you to read the whole piece. (Sorry! But now you know how to make Diet Coke apple pie!) Actually, whether it’s fake is irrelevant, because our reactions to it are what’s of interest to me, not whether there’s a group of extremist women making honey facials while plotting how to snag the cutest mujahideen around. Rather, that’s very much of interest to me—but without being there with them, without listening to their words and witnessing their attitudes, I really can’t comment there. And maybe that’s the real moral here: While there are plenty of Islamic feminists, the extremist agenda that’s (maybe) creating this propaganda prefers its women silent. If it’s a hoax, its grand reveal won’t be able to come from them.

*”The saltier and goofier your clothes, the better. The thing to avoid is any material printed with anchors (you’re trying too hard) or brass buttons (they might scratch the teak on the boat).” Noted.

No, I Still Haven't Stopped Crowing About My Damn Makeover

Kerry Ann King, Dance Instructor, New York City

On the Body of a Dancer

I was always a good dancer, but not built for ballet, aesthetically or physically. I’m not naturally turned out, I don’t have a natural arch in my foot--I spent hours as a child with my mother trying to make arches in my feet. And then I got big boobs! When I was 14 I was taking classes with the Joffrey Ballet School and I was getting a lot of attention from my teachers, but I wasn’t being cast. I decided to ask why because I wanted to know what my future was. My teacher said if I wanted to be a ballerina, I would have to have breast reduction surgery, and I’d have to lose another 10 pounds. I was heartbroken, but I was not going to do that. I was not going to alter my body, even though I loved ballet so much. That was a turning point for me in terms of thinking about beauty. As disappointed as I was that I didn’t meet the aesthetic, I wasn’t going to completely succumb to what was being asked of me. Some of that resistance is just genetic: My mom was an active feminist, my great-grandfather—you know the movie Matewan? He was one of those striking coal miners. I see it in my kids now too.

I went to my first Nia class about six months after my twins were born. I was weak and out of shape, and to be frank, it sounded like it would be easy. But when we started moving what hooked me was that I got the joy I’d always in had dancing--without feeling like I didn’t “look right.” That’s one of the benefits of Nia. You’re supposed to do the technique correctly, but there’s a baseline acknowledgement that our bodies behave differently. Nia allows everyone to have an experience of just doing it.

On Babies and the Body

I know women whose experience of pregnancy and mothering is that they feel their body somehow gets ruined by it. It feels like there’s this desire to not change: “I’m not going to let my body change, I’m not going to let my life change. I’m not gonna let this in.” It’s a way of keeping at bay all the anxiety about the body that comes with having another person inside you. Because it’s freaky! There’s someone inside you! But for me, embracing it made it all easier and left me in a better position on the back end. After I got through the ten years when I was either pregnant or nursing all the time—someone was always using my body for something they needed—I came out stronger, happier, and actually feeling more attractive.

My boys love me in a different way than my girls do. There were a few things about which Freud was correct, and the Oedipal crisis is one of them! They tell me I’m pretty, and they really, truly believe it. I have a lot of loose skin on my belly, and people say to me, “Oh, your abs are so tight, why don’t you get that skin taken away?” I think about it and then I’m like, Am I still me if I do that? And then my sons look at my belly and say, “We love your belly, Mommy! Your wrinkles make a heart!” And, you know, they do! Sons can be very powerful tools for making a woman feel beautiful.

On Observing Beauty in Action

I think for a lot of women, beauty is a tool. We want to attract a mate by being beautiful, or we want to make other women feel a certain way about us—like us, envy us. We’re frequently using it to get something in the world. When you’re constantly in that mind-set, you’re constantly thinking about what someone else is seeing when they look at you. You’re putting yourself in someone else’s mind instead of being in your own: “Does he think I look hot? Does she like my jacket?” Asking what everyone else is thinking is the quintessence of not being in the moment. Whereas when you settle in and feel physically satisfied yourself, instead of thinking, “Is he going to ask for my number?” you become that girl who’s thinking, “Do I like him?” People who are in themselves and in the moment are more attractive. They get more positive attention.

Part of being able to be more in the moment, for me, was age. I wasn’t always comfortable in my body. But now I know its flaws, and I know its advantages, and I’m more willing to take it as it comes. And it’s very powerful for me to spend my time looking at women in my classes, seeing them express themselves and look beautiful. It helps me form my sense of myself and the way I do my work. I teach in Chinatown, and there will be certain Nia movements that are also in tai chi, and lot of my students in that class have been studying tai chi for years at the senior center. I remember giving them an instruction and mentioning something about making your hands into butterflies, and they all did this certain move at the same time. They were beautiful—incredibly so. Also, being around women who are older has shown me that older women can still be sexy. They totally get into all the shimmying! We become attached to the idea that we’re only going to be sexual and beautiful when we’re young, and that adds a veneer of desperation to the idea of staying young, of not getting wrinkles. So for me to see all these women when they’re older, and they’re beautiful and sexy, has been an important learning experience.

On The Power of Being Critical