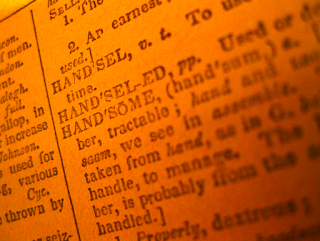

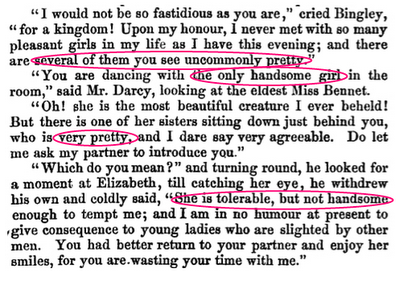

When I wrote about Generation X and how the grunge ethos gave women my age a bit of a reprieve from an uncompromising beauty standard, I was attempting to compare my experience with that of today's teenagers. But after I wrote the post, I realized something major was missing: a teenager. Enter Alexa, a writer I first noticed when she posted at feminist blog The F Bomb, musing on the word pretty, thus laying an irresistible trail of bread crumbs for me to more of her work. Her blog, Blossoming Badass, is a collection of feminist observations and insights ranging from the sociological to the political to the grammatical to the personal. (And did I mention she has impeccable taste in her reading material?) I wanted to know what she, as a teenager, writer, and feminist, thought about her generation's beauty ethos, especially in comparison with what I observed about mine. I'm honored to have Alexa guest post at The Beheld, and would love to know what you—whether you're a baby boomer, GenXer, GenYer, or something else entirely—think about your own generational response to beauty norms.

______________________________________________________

I was thrilled when Autumn asked me to write a response to her post on the beauty norms of Gen X teens from someone who’s a teenager today. And as her post begins with Nirvana, so does mine.

My friend Abby and I are on a sports team together, resulting in a minimum of ninety minutes of school bus rides together a day for over two months. This resulted in copious conversation about essentially everything. As we noticed that our conversations became increasingly confessional as it got darker out, they were dubbed Bus Rides of Truth.

One of these bus rides was about different people and time periods we identified with. Abby’s time periods were the ’60s and the ’90s. I too had a penchant for the ’60s, so we spoke yearningly of Woodstock (her) and the 1969 Miss America Pageant (me), of Janis Joplin (her) and Gloria Steinem (me again). But I didn’t really feel anything about the ’90s. What explained her fondness for the decade we were born? I wondered. Her answer was concise: “Kurt Cobain.”

Abby loves ’90s grunge rock, as well as the whole mentality and style Autumn wrote of as “low-key, a tad sloppy, free-flowing.” Some aspects of ’90s style are still present. Flannel shirts, for example, are still very popular in our high school, but don’t have the same carefree connotation; they’re paired with leggings and Ugg boots, and are left wide open with a tight tank top underneath. Yet no matter how much I tried, I couldn’t correlate the trends of my generation’s attitude toward life with our attitudes toward beauty. I solicited friends and asked them for ideas, but it just wasn’t happening. Everyone had something different to say. Then I realized that was exactly the point.

My generation has our differences branded as diversity. We pride ourselves on individualism. A recent, excellent New York magazine article, entitled “The Kids Are Actually Sort of Alright,” described the generation of recent college graduates, not much older than me, as “delayed, afraid, immature, independent, fame and glory hungry, (ambitious?), weirdly apathetic when it comes to things outside of the internet,” and even, simply, “self-absorbed delusionals.” Although not flattering, I agree. It’s intrinsically human to want to know that you’re different and you’re special. However, in my generation, it’s more of a need than a desire. This has had awesome benefits for us in terms of clothes and beauty as much as everything else. There are trends, but they’re more liberal, in my experience; there isn’t one blanket trend for the entirety of my generation. (There tends to be in middle school, though not by high school—but that’s another story.) In my opinion, the biggest trend in clothes tends to be their tightness. Those oversized blazers of the ’90s are long-forgotten.

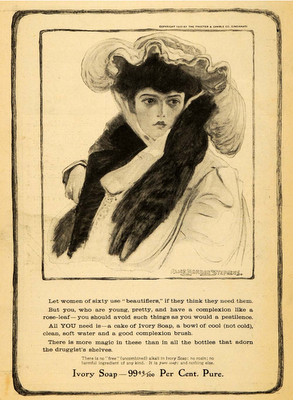

However, this more individualized approach to appearances has led to far different problems, demonstrated with the small sample of girls that I asked, “What pressures do you as an individual feel in terms of your appearance? Regarding weight, makeup, skin, clothes, whatever.”

One classmate, noted for her fondness of clothes and fashion, wrote, “okay so here's my HONEST opinion, albeit an unpopular one. Wanting to look good or be something that is—in your opinion—better is a good thing. If a person wants to change by losing weight, or dressing nicely, or whatever, it doesn't have to be because of the pressure of wanting to fit in… I don't know how it is for everyone else, but I don't look good to please other people, I do it for myself.” This confidence is what the Second Wave feminists so wonderously hoped for one day. Yet a friend from camp remarked, “Personally, as terrible as it may sound, I feel pressure in school to look different and controversial…I feel the pressure to not conform, which I suppose is in itself a form of conforming.” This translates straight to my generation as a whole. And then a teammate provided, “I've had friends who don't think I wear enough make-up (I only wear cover-up), friends who don’t like the way I dress, and friends who don’t even like the way I wear my hair. So, in my opinion there is a lot of pressure from both girls AND guys to look a certain way. I've had guys tell me I’m fat, or that my boobs are too big, or that I need to wear sexier clothing. Personally, I don’t care terrribly much, so I just tell them to fuck off, but I've felt the pressure to change myself for better or for worse.”

So as I sit here, listening to the Nirvana MTV Unplugged CD I borrowed from Abby, what conclusion could I draw? These girls had utterly different views on how this generation influenced how they felt about their bodies and fashion. Still, I identified completely with all of them. While the pressure to brand ourselves through our clothes and overall look might be greater than it was for previous generations, that didn’t seem quite satisfactory. And then I realized another reason I’d had difficulty summing up my generation’s attitudes toward beauty: I can’t diagnose a generation still in formation. Maybe that seems like a cop-out, but the 16-year-olds of 1991 weren’t able to identify themselves as disillusioned in the midst of their genesis. Like they were, we’re all still in the throes of it, straightening our hair or deliberately not, wondering whether to button up our flannel shirts.

Yet there’s one thing we’ve got going for us that can only serve us well: All of our sharing of feelings and expounding of individuality has led to a far larger discourse about how we feel about our bodies and deal with appearances when compared with our predecessors. An aspect of Gen X fashion was most definitely a forced not caring, but our culture didn’t yet have a ready vocabulary for Generation X teens to discuss that feigned nonchalance with one another. My generation has the benefit of that vocabulary, and from that spring things like Abby’s and my Bus Rides of Truth. There’s commiseration between girls, both silent and not. We can all see how hard everyone is trying to look like they’re not; it’s a topic that’s spoken about. For now, it’s only being spoken about; for it to actually impact the amount of effort we spend on ourselves, we’ll need to keep the conversation going. If we can make that happen, I think that in twenty years, we might be able to find the positivity in our generation’s mentality as well.