What's going on in beauty this week, from head to toe and everything in between.

From Head...

Headucation: African-American hair salons have a long history of being hotbeds of activism. That thrives today, but the Beauty Is It salon in Staten Island is making it official with a news exhibit called "Black Women in American Culture and History"—including, of course, a nod to Madame CJ Walker.

...To Toe...

The pedicure of the future: When the Burgundy Girls dreamed up this galactic nail treatment they were picturing it for manicures, but I'm more apt to go wild on my toes than my hands. Am I alone on this? Either way, this look is glittery gorgeousness.

...And Everything In Between:

Girltanked: Know some young female innovators? (Of course you do.) Girltank, a new think tank of young female social entrepreneurs across the globe, wants to know about them. There are so many young women doing incredible things worldwide; Girltank aims to help them connect with one another and give them access to opportunities and resources that help shape communities and conversations across the world. This might not seem to have much to do with beauty, but it does: The public perception of young women is that they're there to be looked at, or that they need "our help." Girltank aims to change that perception by showing young women as change-makers and contributors to society. If you know of any women who fit the bill, visit Girltank's Facebook page and let them know! (There are raffle prizes too, as added incentive, including a $100 package from Lush.)

Corrupt much?: The beauty biz leads in consumer complaints in Singapore, beating out even the sleaze-ridden timeshare industry.

If you've got a problem, yo I'll solve it: I will forever get a thrill out of reading marketing analysis, as it reveals exactly how campaigns are designed to work on us. This one comes from market analysis firm NPD in regards to men's skin care: "There is a feeling that facial skin care products are not needed unless you have a specific skin problem... For men to use a product, he first must be aware that there is an underlying need that requires addressing," says industry analyst Karen Grant. That is, tell him what's wrong with him, then fix him. Sound familiar?

Sample sale: Birchbox-like cosmetics sampling services are catching on in Korea—because the sale of samples was banned last year.

Swift justice: Twenty-five years after being arrested for selling cosmetics fakes, a New Delhi man has finally been sentenced to a year of community service.

Straw feminist: I've been reading the Tumblr Pop Feminist Perblog for a while, and this screed shows why. I don't agree with every word she's saying here but she succinctly breaks down the dangers of posing the performance of traditional femininity as subversive for its own sake, and also lays out a point that's frighteningly easy to overlook in appearance-related discussions of feminism: "Show me a feminist who is saying we can't be feminine. Seriously, show me a feminist who is saying we can't be feminine."

Meow: Intellectually, I buy the argument that Hello Kitty might contain hidden forms of cuteness-as-power in a postindustrial society. Practically, I can't stand the little bitch. Either way, this piece is interesting. "The gift under capitalism is the moment that circulation is affected by the introduction of an irreducible social aspect. As the gift of cuteness, then, Hello Kitty becomes a sort of value-analog that works by exempting itself from circuits of valorization."

Бунт Grrl: If you doubt the potential for the forcefulness of feminine motifs, check out Pussy Riot, a Russian feminist punk band protesting the current political climate under Putin. These summer-dress-clad performers are downright fierce, and the potency of their message has more weight than all too many punk bands in the U.S.

Stolen pink: I've been turned off "breast cancer kitsch" for a while, but if I hadn't been, the lede of this Anna Holmes piece in Washington Post would seal the deal. Apparently the pink ribbon was a grassroots effort from a survivor; when Self magazine and Estee Lauder asked if they could co-opt it in their campaign, she turned them down, fearing commercialization of her ordeal. But the show must go on: They tweaked the color, put pink on parade, and now we can all buy pink products (with nary an assurance a dime goes toward cancer research).

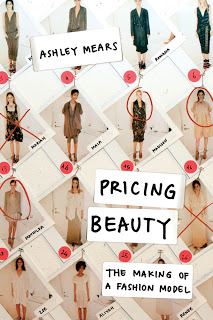

Economic models: The Economist covers the trend within the modeling industry of hiring "more aspirational young women" rather than the "very young, impressionable models" that have overwhelmingly composed the modeling workforce—think students and do-gooders. I think Sally Davies is onto something when she casually posits (and by "casually" I mean "on Twitter," where she called my attention to the piece) that "Maybe beauty's social premium has gone up everywhere, so industry trades prestige for pay and also creates more internal hierarchy."

Muslim makeup: Halal cosmetics and toiletries make up 9% of the global halal market, and demand may be growing. Halal cosmetics are basically vegan cosmetics with certification, so I'm surprised we don't see more "certified halal" branding. Oh wait, never mind.

Prioritizing biology: The writer of this Slate piece is talking about Cynthia Nixon's statement that, for her, being gay was a choice—and that that shouldn't matter. But the larger point ties into the idea I was getting into earlier this week: Why do we prioritize biology over all else? In the gay rights movement certainly it was helpful at one point to frame sexual orientation biologically; it helped plenty of people understand that it was no more a choice than heterosexuality is for the majority of the population. But just as biology isn't what makes sexual orientation a perfectly fine way to live, neither do biological tendencies to prefer symmetrical faces or whatever mean we shouldn't question social construction of beauty. (Thanks to Rachel for the link.)

Default browser: Baby boomers buy more cosmetics online than other age groups, which makes total sense to me. I wouldn't buy makeup online unless I knew it was exactly what I wanted: exact shade, exact consistency, exact size, etc. And I'm guessing by the time I'm 50, I'll have damn well figured that out.

Photoshopesque: We've heard ad nauseam about how classic paintings depicted fuller-figured women than what we tend to favor now—but this collection shows us, by retouching everything from Botticelli to Velazquez. Yikes! (Thanks to Meaghan for pointing me toward it.)

The loss of addiction: Medicinal Marzipan on the feeling of loss that comes with healing from emotional eating: "I miss the quick-fix, the bowl of beans and rice, the easy remedy that I could provide myself with the contents of my cupboards. Yes, I always knew this fix was fickle and short-lived, but in that moment, cheese solved most problems." It's a painful part of recovery, that sense of loss, but it's important to talk about.

What does "flattering" really mean?: "To me, flattering is another form of size policing and body fascism." I don't entirely agree with this piece at Persephone—I use the word flattering to mean I look how I want to look, and sometimes that absolutely includes concealing certain parts and highlighting others, which, you know, conforms to beauty standards. But the article is thought-provoking, and I know that I make a point to never use "flattering" as code for "It makes you look thinner" when talking to someone else. (So why use it for myself? Hmm.)

Books abound!: Congratulations to Elissa at Dress With Courage for her soon-to-be-published Thrifting 101, and to Kjerstin Gruys, who just signed with Penguin to publish a book about her year without mirrors. Excellent, excellent!

More of me: Don't believe a word you read about me in Us magazine, the damned vultures. Instead, read these two interviews with me from two excellent organizations: Ma'yan, a research and education nonprofit examining identity issues facing Jewish girls, and Radar Productions, a literary nonprofit founded by Michelle Tea focused on giving voice to LGBTQ experiences. I don't blog much about blogging, because I gather that's not what you're here for, but if you're curious to know more about my thinking on what goes on The Beheld you may find them interesting.

Podcasting: Sally McGraw for Strong, Sexy & Stylish leads a discussion on the connection between looking great and feeling confident. She's pretty much the master of demonstrating why looking your best is a beginning, not an ending, to being your best self, so tune in, eh?

Comfort and style: Decoding Dress continues her series on discomfort and fashion by engaging with readers' comments to surge toward a thesis of fashion and comfort as social control. (Have I mentioned lately how much I think you all should be reading her?)

Have you ever seen a dermatologist?: Courtney at Those Graces asks why we're more willing to cover up our skin than to fix it. Yes, "fix" is a loaded term, but the point is that plenty of women spend money on concealers and foundations instead of going to a dermatologist, when really, if you have a genuine skin problem, that's where you should be going. Is it the paperwork? The hassle? The fact that it's less fun to visit a doctor than play at Sephora?

Like, layperson linguistics, totally: How does your voice influence the ways people think of you? A Valley girl thoughtfully shares her story.

From Head...

Headucation: African-American hair salons have a long history of being hotbeds of activism. That thrives today, but the Beauty Is It salon in Staten Island is making it official with a news exhibit called "Black Women in American Culture and History"—including, of course, a nod to Madame CJ Walker.

...To Toe...

The pedicure of the future: When the Burgundy Girls dreamed up this galactic nail treatment they were picturing it for manicures, but I'm more apt to go wild on my toes than my hands. Am I alone on this? Either way, this look is glittery gorgeousness.

...And Everything In Between:

Girltanked: Know some young female innovators? (Of course you do.) Girltank, a new think tank of young female social entrepreneurs across the globe, wants to know about them. There are so many young women doing incredible things worldwide; Girltank aims to help them connect with one another and give them access to opportunities and resources that help shape communities and conversations across the world. This might not seem to have much to do with beauty, but it does: The public perception of young women is that they're there to be looked at, or that they need "our help." Girltank aims to change that perception by showing young women as change-makers and contributors to society. If you know of any women who fit the bill, visit Girltank's Facebook page and let them know! (There are raffle prizes too, as added incentive, including a $100 package from Lush.)

Corrupt much?: The beauty biz leads in consumer complaints in Singapore, beating out even the sleaze-ridden timeshare industry.

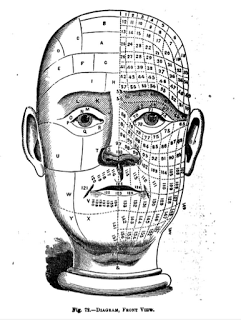

If you've got a problem, yo I'll solve it: I will forever get a thrill out of reading marketing analysis, as it reveals exactly how campaigns are designed to work on us. This one comes from market analysis firm NPD in regards to men's skin care: "There is a feeling that facial skin care products are not needed unless you have a specific skin problem... For men to use a product, he first must be aware that there is an underlying need that requires addressing," says industry analyst Karen Grant. That is, tell him what's wrong with him, then fix him. Sound familiar?

Sample sale: Birchbox-like cosmetics sampling services are catching on in Korea—because the sale of samples was banned last year.

Swift justice: Twenty-five years after being arrested for selling cosmetics fakes, a New Delhi man has finally been sentenced to a year of community service.

Straw feminist: I've been reading the Tumblr Pop Feminist Perblog for a while, and this screed shows why. I don't agree with every word she's saying here but she succinctly breaks down the dangers of posing the performance of traditional femininity as subversive for its own sake, and also lays out a point that's frighteningly easy to overlook in appearance-related discussions of feminism: "Show me a feminist who is saying we can't be feminine. Seriously, show me a feminist who is saying we can't be feminine."

Meow: Intellectually, I buy the argument that Hello Kitty might contain hidden forms of cuteness-as-power in a postindustrial society. Practically, I can't stand the little bitch. Either way, this piece is interesting. "The gift under capitalism is the moment that circulation is affected by the introduction of an irreducible social aspect. As the gift of cuteness, then, Hello Kitty becomes a sort of value-analog that works by exempting itself from circuits of valorization."

Бунт Grrl: If you doubt the potential for the forcefulness of feminine motifs, check out Pussy Riot, a Russian feminist punk band protesting the current political climate under Putin. These summer-dress-clad performers are downright fierce, and the potency of their message has more weight than all too many punk bands in the U.S.

Stolen pink: I've been turned off "breast cancer kitsch" for a while, but if I hadn't been, the lede of this Anna Holmes piece in Washington Post would seal the deal. Apparently the pink ribbon was a grassroots effort from a survivor; when Self magazine and Estee Lauder asked if they could co-opt it in their campaign, she turned them down, fearing commercialization of her ordeal. But the show must go on: They tweaked the color, put pink on parade, and now we can all buy pink products (with nary an assurance a dime goes toward cancer research).

Economic models: The Economist covers the trend within the modeling industry of hiring "more aspirational young women" rather than the "very young, impressionable models" that have overwhelmingly composed the modeling workforce—think students and do-gooders. I think Sally Davies is onto something when she casually posits (and by "casually" I mean "on Twitter," where she called my attention to the piece) that "Maybe beauty's social premium has gone up everywhere, so industry trades prestige for pay and also creates more internal hierarchy."

Muslim makeup: Halal cosmetics and toiletries make up 9% of the global halal market, and demand may be growing. Halal cosmetics are basically vegan cosmetics with certification, so I'm surprised we don't see more "certified halal" branding. Oh wait, never mind.

Prioritizing biology: The writer of this Slate piece is talking about Cynthia Nixon's statement that, for her, being gay was a choice—and that that shouldn't matter. But the larger point ties into the idea I was getting into earlier this week: Why do we prioritize biology over all else? In the gay rights movement certainly it was helpful at one point to frame sexual orientation biologically; it helped plenty of people understand that it was no more a choice than heterosexuality is for the majority of the population. But just as biology isn't what makes sexual orientation a perfectly fine way to live, neither do biological tendencies to prefer symmetrical faces or whatever mean we shouldn't question social construction of beauty. (Thanks to Rachel for the link.)

Default browser: Baby boomers buy more cosmetics online than other age groups, which makes total sense to me. I wouldn't buy makeup online unless I knew it was exactly what I wanted: exact shade, exact consistency, exact size, etc. And I'm guessing by the time I'm 50, I'll have damn well figured that out.

What would the Venus of Urbino look like with a tummy tuck? Find out here.

Photoshopesque: We've heard ad nauseam about how classic paintings depicted fuller-figured women than what we tend to favor now—but this collection shows us, by retouching everything from Botticelli to Velazquez. Yikes! (Thanks to Meaghan for pointing me toward it.)

The loss of addiction: Medicinal Marzipan on the feeling of loss that comes with healing from emotional eating: "I miss the quick-fix, the bowl of beans and rice, the easy remedy that I could provide myself with the contents of my cupboards. Yes, I always knew this fix was fickle and short-lived, but in that moment, cheese solved most problems." It's a painful part of recovery, that sense of loss, but it's important to talk about.

What does "flattering" really mean?: "To me, flattering is another form of size policing and body fascism." I don't entirely agree with this piece at Persephone—I use the word flattering to mean I look how I want to look, and sometimes that absolutely includes concealing certain parts and highlighting others, which, you know, conforms to beauty standards. But the article is thought-provoking, and I know that I make a point to never use "flattering" as code for "It makes you look thinner" when talking to someone else. (So why use it for myself? Hmm.)

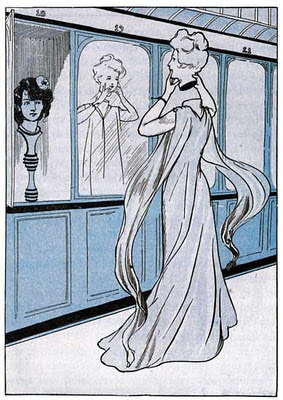

Books abound!: Congratulations to Elissa at Dress With Courage for her soon-to-be-published Thrifting 101, and to Kjerstin Gruys, who just signed with Penguin to publish a book about her year without mirrors. Excellent, excellent!

More of me: Don't believe a word you read about me in Us magazine, the damned vultures. Instead, read these two interviews with me from two excellent organizations: Ma'yan, a research and education nonprofit examining identity issues facing Jewish girls, and Radar Productions, a literary nonprofit founded by Michelle Tea focused on giving voice to LGBTQ experiences. I don't blog much about blogging, because I gather that's not what you're here for, but if you're curious to know more about my thinking on what goes on The Beheld you may find them interesting.

Podcasting: Sally McGraw for Strong, Sexy & Stylish leads a discussion on the connection between looking great and feeling confident. She's pretty much the master of demonstrating why looking your best is a beginning, not an ending, to being your best self, so tune in, eh?

Comfort and style: Decoding Dress continues her series on discomfort and fashion by engaging with readers' comments to surge toward a thesis of fashion and comfort as social control. (Have I mentioned lately how much I think you all should be reading her?)

Have you ever seen a dermatologist?: Courtney at Those Graces asks why we're more willing to cover up our skin than to fix it. Yes, "fix" is a loaded term, but the point is that plenty of women spend money on concealers and foundations instead of going to a dermatologist, when really, if you have a genuine skin problem, that's where you should be going. Is it the paperwork? The hassle? The fact that it's less fun to visit a doctor than play at Sephora?

Like, layperson linguistics, totally: How does your voice influence the ways people think of you? A Valley girl thoughtfully shares her story.