When I initially embarked on my mirror fast, I hadn't really given thought to the ways that media has treated mirrors. Throughout the month, though, friends kept referring me to songs, films, and stories that explore mirrors. Here they are, along with others that I either love or that this month has shed new light on:

1) Peeping Tom, 1960: There's a reason slumber-party favorite "Bloody Mary" persisted from my mother's generation to mine: Mirrors can be creepy! And films don't hesitate to take advantage: Candyman, Poltergeist, Black Swan, The Shining, and, of course, Mirrors, all feature mirrors as either a central plot point or motif. Even some of the best moments in my beloved Twin Peaks involve mirrors. But Peeping Tom takes the cake. Michael Powell's story of a young man/serial killer whose life is ruled by surveillance features a terrifying mirrored climax. Overall it's more of a comment on the role of documentation (we learn along the way that our villain is the way he is because his father constantly filmed him growing up—now seen as not intrusive, but expected), but mirrors wind up being an essential part of his hijinx.

2) "Mirrors," Carol Shields: A short story about a couple who spends every summer without a mirror. We see how over the lifetime of a marriage, this gesture's significance shifts, from accidental to a meditative delight to a clever cover-up for shame, to, of course, the way we function as mirrors for one another. " 'You remind me of someone,' she said the first time they met. He knew she meant that he reminded her of herself." (Thanks to Terri at Rags Against the Machine for the tipoff!)

3) "Man in the Mirror," Michael Jackson. Bear with me here, people! Cheesy, simplistic, overwrought, sure. But it's a perfect example of the ways in which the mirror deludes us. Were the singer any other pop star, it wouldn't haunt me so. With this singer with this history, though, the lyrics become poignant, painful. The man in the mirror is supposed to reflect back a potentially better self. But it's impossible for me not to think of the allegations of pedophilia against Jackson when hearing: "I see the kids in the street / With not enough to eat / Who am I, to be blind / Pretending not to see their needs." I have no doubt in my mind that whatever Michael Jackson did to children, he did not because he was a monster but because he was so damaged as to see himself a child as well—a rich, famous, otherworldly child who on some level probably believed the bizarre Neverland he set up was, indeed, fulfilling children's needs. The mirror didn't reflect back what the rest of us saw. And it was a tragedy for everyone.

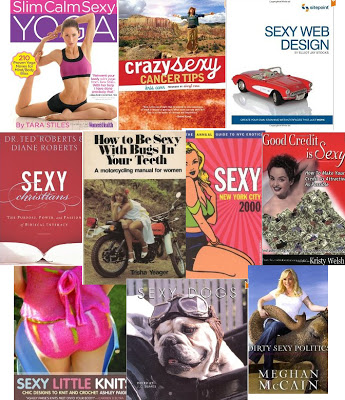

4) Mirror Mirror Off the Wall: So how awesome was it when, two days into my mirror fast, I hear from Kjerstin Gruys, a sociology Ph.D. candidate at UCLA who is abstaining from mirrors for a year? She taught herself to apply makeup without a mirror; she's not looking at photos of herself—oh, and she's getting married in October. With her thoughtful mix of personal stories, sociology background, and wholeheartedly lady-positive approach (she's also a volunteer with the amazing About-Face), Mirror Mirror Off the Wall is an engaging, amusing, sincere blog, and I look forward to continuing to read about Kjerstin's insights.

5) Radiolab's "Mirror Mirror": Entertaining look at the science behind reflection, from the molecular level to the arena of psychology (including a story of a man who claims changing his hair part to match his mirror self wound up changing his life). (Thanks to Andréa at Remembering Self for sending this my way!)

6) "Funny Is Never Forever," Richard Melo: This short story is actually one of many connected super-short stories collected at fiction-social-networking site Red Lemonade; it's about an American nursing hospital in Haiti in the 1950s. It's the second story here that particularly interests me, the intimacy of having both a personal double and a mirror double; Melo's work consistently has a tender, gentle pulse (as evidenced by his novel Jokerman 8), and this collection is no different.

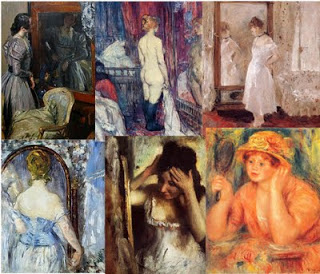

7) "Mirror," Sylvia Plath: Says the mirror-narrator of Plath's poem, "In me she has drowned a young girl, and in me an old woman / Rises toward her day after day, like a terrible fish." The divided self shows up repeatedly in her work; even her thesis at Smith was titled "The Magic Mirror: A Study of the Double in Two of Dostoevsky's Novels." One of her last poems, "Contusion," even ends with the double's retreat after its initial rush: "The heart shuts / The sea slides back / The mirrors are sheeted."

8) Mirror Mirror: a History of the Human Love Affair With Reflection, by Mark Pendergrast: From the Venetian mirror-makers who enjoyed cultural prestige but who were kept prisoner on Murano island, to divination using mirrors, to the 1928 sample room at Macy's that featured entirely mirrored surfaces and led to a near-frenzy, this complete history of mirrors is interesting on a technical level, though I longed to know more about who was doing all that looking during the eras he describes at length.

9) "Snow White", the Brothers Grimm, translated by D.L. Ashliman: From the poisoned comb to the too-tight corset that the evil queen uses in her homicide attempts, this story is an incredible comment on the trappings of femininity. (I'd forgotten that the original ending has the queen dancing herself to death in heated iron shoes. Yowza!) But it's the mirror that began it all: The queen was fine and dandy being superlatively gorgeous until the mirror told her that someone out there (a seven-year-old!) could do her a thousand times better. It makes a fine ending for Anne Sexton's retelling as well: "Meanwhile Snow White held court / rolling her china-blue doll eyes open and shut / and sometimes referring to her mirror / as women do."

10) "I'll Be Your Mirror," The Velvet Underground: Early in my mirror fast I had dinner with my friend Lindsay, who covers the beauty beat at The Daily News, bringing things like makeup ad falsities to New Yorkers. She told me that she'd be my mirror, "as Nico sang," and because both Lindsay and The Velvet Underground are extraordinarily cool and I want to be extraordinarily cool too, I pretended that I knew the reference. Luckily, I didn't have to pretend for long, because on the morning of my birthday I awoke to "I'll Be Your Mirror" waiting for me in my inbox from another friend. Aww, you guys! "When you think the night has seen your mind / That inside you're twisted and unkind / Let me stand to show that you are blind / ... 'Cause I see you." Short, plaintive, and, of course, extraordinarily cool.

Anna Massey learns the creepmaster's secrets. Peeping Tom, 1960.

2) "Mirrors," Carol Shields: A short story about a couple who spends every summer without a mirror. We see how over the lifetime of a marriage, this gesture's significance shifts, from accidental to a meditative delight to a clever cover-up for shame, to, of course, the way we function as mirrors for one another. " 'You remind me of someone,' she said the first time they met. He knew she meant that he reminded her of herself." (Thanks to Terri at Rags Against the Machine for the tipoff!)

No message could have been any clearer.

3) "Man in the Mirror," Michael Jackson. Bear with me here, people! Cheesy, simplistic, overwrought, sure. But it's a perfect example of the ways in which the mirror deludes us. Were the singer any other pop star, it wouldn't haunt me so. With this singer with this history, though, the lyrics become poignant, painful. The man in the mirror is supposed to reflect back a potentially better self. But it's impossible for me not to think of the allegations of pedophilia against Jackson when hearing: "I see the kids in the street / With not enough to eat / Who am I, to be blind / Pretending not to see their needs." I have no doubt in my mind that whatever Michael Jackson did to children, he did not because he was a monster but because he was so damaged as to see himself a child as well—a rich, famous, otherworldly child who on some level probably believed the bizarre Neverland he set up was, indeed, fulfilling children's needs. The mirror didn't reflect back what the rest of us saw. And it was a tragedy for everyone.

4) Mirror Mirror Off the Wall: So how awesome was it when, two days into my mirror fast, I hear from Kjerstin Gruys, a sociology Ph.D. candidate at UCLA who is abstaining from mirrors for a year? She taught herself to apply makeup without a mirror; she's not looking at photos of herself—oh, and she's getting married in October. With her thoughtful mix of personal stories, sociology background, and wholeheartedly lady-positive approach (she's also a volunteer with the amazing About-Face), Mirror Mirror Off the Wall is an engaging, amusing, sincere blog, and I look forward to continuing to read about Kjerstin's insights.

5) Radiolab's "Mirror Mirror": Entertaining look at the science behind reflection, from the molecular level to the arena of psychology (including a story of a man who claims changing his hair part to match his mirror self wound up changing his life). (Thanks to Andréa at Remembering Self for sending this my way!)

6) "Funny Is Never Forever," Richard Melo: This short story is actually one of many connected super-short stories collected at fiction-social-networking site Red Lemonade; it's about an American nursing hospital in Haiti in the 1950s. It's the second story here that particularly interests me, the intimacy of having both a personal double and a mirror double; Melo's work consistently has a tender, gentle pulse (as evidenced by his novel Jokerman 8), and this collection is no different.

"I am silver and exact": Sylvia Plath

8) Mirror Mirror: a History of the Human Love Affair With Reflection, by Mark Pendergrast: From the Venetian mirror-makers who enjoyed cultural prestige but who were kept prisoner on Murano island, to divination using mirrors, to the 1928 sample room at Macy's that featured entirely mirrored surfaces and led to a near-frenzy, this complete history of mirrors is interesting on a technical level, though I longed to know more about who was doing all that looking during the eras he describes at length.

9) "Snow White", the Brothers Grimm, translated by D.L. Ashliman: From the poisoned comb to the too-tight corset that the evil queen uses in her homicide attempts, this story is an incredible comment on the trappings of femininity. (I'd forgotten that the original ending has the queen dancing herself to death in heated iron shoes. Yowza!) But it's the mirror that began it all: The queen was fine and dandy being superlatively gorgeous until the mirror told her that someone out there (a seven-year-old!) could do her a thousand times better. It makes a fine ending for Anne Sexton's retelling as well: "Meanwhile Snow White held court / rolling her china-blue doll eyes open and shut / and sometimes referring to her mirror / as women do."

Nico and Lou Reed are cool. Cool! So cool.

10) "I'll Be Your Mirror," The Velvet Underground: Early in my mirror fast I had dinner with my friend Lindsay, who covers the beauty beat at The Daily News, bringing things like makeup ad falsities to New Yorkers. She told me that she'd be my mirror, "as Nico sang," and because both Lindsay and The Velvet Underground are extraordinarily cool and I want to be extraordinarily cool too, I pretended that I knew the reference. Luckily, I didn't have to pretend for long, because on the morning of my birthday I awoke to "I'll Be Your Mirror" waiting for me in my inbox from another friend. Aww, you guys! "When you think the night has seen your mind / That inside you're twisted and unkind / Let me stand to show that you are blind / ... 'Cause I see you." Short, plaintive, and, of course, extraordinarily cool.