Hot is tanned, free of body hair, and in a miniskirt. Hot likes to party, and we know better than to take hot too seriously. Hot is younger than most; Google will find 24 million hot women for you, but 31 million hot girls. Hot is purchased, packaged, and with a firm price. Hot is a series of illusions; you may wake up with the mantle of hot, but you weren't born that way. Hot is Miami. Hot is Venice Beach. Hot is JWoww.

I have to fight here to not simply spew against

hot. But my distaste for the word shines through: To me, it represents a crude packaging of the spark that might give a person the "heat" from which our use of

hot should derive.

Hot removes its opposite—cold—leaving us lopsided, with no yin to balance out the yang that

hot thrusts upon us. And is it any surprise that yin's energy—if you believe in this hippie eastern chi stuff—is the cool, lunar feminine, whereas yang's dry heat is associated with masculinity?

It's not a stretch to imagine that with the terminology of heat being applied to everything from temperament (1100s), food (1540s), scent (1600s), jazz (1912), and radioactivity (1940s), that

hot might have been loosely applied to women throughout the ages. Indeed,

hot has applied to our physical passions since the 1590s, and my beloved 1894 Webster's gives "Lustful; lewd" as one of its definitions.

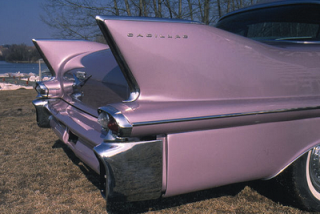

When America was on the brink of the (supposed) sexual revolution, heat cropped up frequently in film titles—but it was still being used to describe a situation, not a woman.

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958, though the play was published in 1955),

The Long, Hot Summer (1958), and

Some Like It Hot (1959) clustered around the precipice of revolution, and it seems unlikely that this was a coincidence (

Some Like It Hot's working title was

Not Tonight, Josephine). And we weren't quite ready to take the plunge into woman-as-heat:

Too Hot to Handle (1960), starring Jayne Mansfield, who had been on loan to a British company when

she became too hot to handle in the States, had to be released in the U.S. as

Playgirl After Dark. But beginning in the 1960s, we took the plunge to explicitly calling women

hot:

Hot-Blooded Woman (1965) rode the sexploitation wave, followed by a flurry of ambiguously titled films whose packaging made it clear that

hot references the woman, not what's outside.

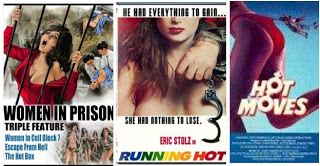

The Hot Box (1972) remains a jewel in the crown of women-in-prison flicks (after—what else?—

Caged Heat);

Running Hot and

Hot Moves (both 1984) maintained the surveillance of hot women.

Then, of course, came Paris Hilton, with her 2005 trademarking

(literally) of "That's hot." She wasn't speaking only of women, of course; it seemed to be a catch-all phrase that could apply to anything from shoes to lip balm to the Middle East. Yet her lyrengeal, lackadaisical utterance of "That's hot" clearly contained anything but passion, leaving only Hilton's self-presentation as a branding of hotness. In a sort of airy philosophical way I'd like to declare her turnaround of "That's hot"—shifting the focus from herself to the world around her—as a reclamation of

hot. In truth, however, Hilton is far too savvy of a marketer to have chosen that terminology without being keenly aware of its reflexive effect upon her image. Hilton's tanned, dyed, refurbished appearance epitomizes hot and its machinations. By being a distant yet explicitly available persona, she illustrates the trap of

hot: It's not that you'll get burned if you come too close; it's that you might see that you're looking at a Yule Log DVD, not a live fire.

Hot should be synonymous with

sexy, yet it's not.

Sexy should be more blatant, more crude, more vulgar—it mentions s-e-x!—but the plastic quality

hot connotes makes

sexy seem its authentic, primal alternative.

Hot gets to the core of objectification: A woman is not intrinsically hot; instead, the viewer becomes heated upon seeing her and attributes his own reaction to her essence. She becomes

hot once seen through his eyes, not before. The yin and yang again: Men and women alike describe women as

beautiful. But when we speak of her as

hot, we understand that her hotness exists only in the context of being seen by others; it's knowing that

she will be viewed that makes her

hot. She is not

hot at home, by herself, doing laundry or dozing or dancing, even as she might be

pretty or

beautiful. Nothing can exist in a vacuum: not sound, color, smell, or temperature. In physics and in the public sphere alike, nothing can be hot in a vacuum. It requires energy—yours, the viewer's—in order to exist.